Tuesday, April 29, 2025

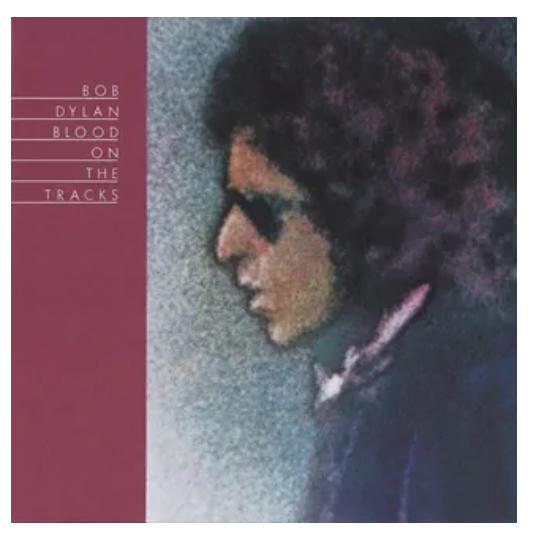

The view from 1975: BLOOD ON THE TRACKS

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

A THICK PARAGRAPH CONDENSING THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BOB DYLAN AND LEONARD COHEN

Friday, September 24, 2021

A NOTE

Bob Dylan performed at New York's esteemed Carnegie Hall, for which he additionally wrote the program notes. Titled My Life in a Stolen Moment, it's a long, rambling length of free verse poetry that is an intriguing example of Dylan juvenilia. A self- conscious and entirely awkward combination of Beat style first-thought-best-thought idea and the unlettered eloquence of the deep feeling poor white, it purports to be the true telling of Dylan's upbringing in small-town Minnesota.It's not a reliable document. As an autobiography, I wouldn't trust a word of it. Dylan embellished his story from the beginning. Inconsistencies and incongruities in his stated timeline were noted early on. I remember that Sy and Barbara Ribakove were suspicious of Dylan's accounting of his life back in 1966 with their book "Folk-Rock: The Bob Dylan Story." All the fabulation has certainly given a couple of generations of Dylan obsessives much to sift through and write books about. It's a poem, of course, but not a good one. What had always irritated me about Dylan's writing was his affectation of the poor, white rural idiom. It's dreadful, unnatural sounding as you read it (or listen to it from his early recordings). While it's one thing to be influenced by stories of hobo life, the Great Depression, and to use the inspiration to find one's uniquely expressive voice as a writer or poet, what Dylan does here ranks as some of his most pretentious, awkward, and preening writing. One can argue in Dylan's defense with the vague idea of negative capability, but that holds water only if the writing is great and the writer is possessed by genius. Of course, Dylan is/was a genius, but this was something he wrote when he was merely talented and audacious. Genius hadn't bloomed yet. This bucolic exercise has always been an embarrassment, juvenilia that sounds juvenile.

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

QUEEN JANE APPROXIMATELY

When your mother sends back all your invitationsAnd your father, to your sister, he explainsThat you're tired of yourself and all of your creationsWon't you come see me, Queen Jane?Won't you come see me, Queen Jane?

Now, when all of the flower ladies want back what they have lent youAnd the smell of their roses does not remainAnd all of your children start to resent youWon't you come see me, Queen Jane?Won't you come see me, Queen Jane?

Now, when all the clowns that you have commissionedHave died in battle or in vainAnd you're sick of all this repetitionWon't you come see me, Queen Jane?Won't you come see me, Queen Jane?

Monday, May 31, 2021

TARANTULA

Unresponsible Black Nite Crash

the united states is Not soundproof – you might think that nothing can reach those tens of thousands living behind the wall of dollar – but your fear Can bring in the truth … picture of dirt farmer – long johns – coonskin cap – strangling himself on his shoe – his wife, tripping over the skulls – her hair in rats – their kid is wearing a scorpion – the scorpion wears glasses – the kid, he’s drinking gin – everybody has balloons stuck into their eyes – that they will never get a suntan in mexico is obvious – send your dollar today – bend over backwards … or shut your mouths forever

the bully comes in – kicks the newsboy

you know where – & begins ripping away

--from Tarantula

The book goes on like this, one-liners of light bulb brilliance extended to the breaking point of where all associations are gone, and the brain is dead with the ravages of whatever drugs were being passed around the tour bus and found their way into the hotel room. All that can be done in the center of the night when the rest of the hotel room is either asleep or murmuring their own serenades to the dawn no one is sure will for them is to type, even more, an attempt to fill the page with a verbal world that is rhythm, cadence and shattered images crushed together in a representation of the existence that assaults the senses when exhaustion is passed by. Consciousness seems to hover by a delicate string between one last grand illumination and the final resolute darkness.

Well, yes, if you made through that tortured sentence and its unhinged and perhaps uninteresting associations, you correctly detect a hint of parody in my construction or lack of building. This is to suggest that the fault of the Dylan book is not his exuberance as word slinger or the genius he has at his most manic moments to come up with a punctuated stammer that resides very close to poetic genius--no, the fault is the mistake many a young man or woman jacked up on drugs and coffee and unfiltered cigarettes, that is the attempt to live in a permanent present tense. No past, no future, just right now, always, just us, the things in the room or in the street, things with names or no names, just us seeing, uttering names, and slapping the labels on anything that does not match. Good poetry takes time to...catch its breath, reflect, to...discover things, ideas, connections, what have you, the would-be bard hadn't the slightest idea existed in any sense. As startling as Tarantula's language seems at first, it stops surprising you even in the book's short length because the writing itself seems the very thing from which writing, as a process, was supposed to for a period free you from distractions. The writing seems a distraction. One might compare the book entirely to the proverbial over-stuff pantry that finally bursts open through the doors.

He needed to wrap up his investigations into his more obscure imaginings. He gave you something to talk about. Tarantula was written on the road, in hotel rooms, on tour, rattled off in high doses of speed, and maybe other drugs too inane to bother talking about, and it certainly reads like it, snub-nosed Burroughs, Kerouac without the jivey swing. Some parts make you laugh, some good lines abound. Still, it suffers in that readers wanted their hero, the poet of their generation, to write a genuinely good of poetry or some such thing, with true believers tying themselves in self-revealing knots to defend the book that is interesting as an artifact to the historical fact of Dylan's fame and influence and not much else. There is a part I like, effective as poetry, a bit of self-awareness that shows that Dylan realizes that his persona is false, a conspiracy between himself and the major media and that somewhere in the future, he might have to account for the construction of the whole matter.

Monday, May 24, 2021

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED

Saturday, August 8, 2020

DON'T SING DYLAN LYRICS, DANCE THEM!

Sunday, August 2, 2020

DYLAN IS NOT A POET, BUT HE PLAYS ONE ON TV

1.

|

| photograph by Jim Marshall |

An old peeve, this: Bob Dylan is not a poet. He is a songwriter. What he does is significantly different than what a poet does. In any relevant sense, the best of what poetry offers is read off the page, sans melody from accompanying guitar or piano and a convincingly evocative voice. The poet's musical sense, rhythmic properties, and other euphonious qualities are derived from the words and their clever, ingenious combinations alone. A reader may appreciate the words, the rhymes, the cadences, the melodious resonance, and dissonance, as the case may be, but all this comes from the poem's language alone, on the page, without music. The musicality we speak of when addressing such rich and soul-stirring sounds of nouns and adjectives conjoined has everything to with the poet extending the limits of everyday speech. You can read Shakespeare to full literary potential, I think, because his verse, in the guise of dialogue, still satisfies as writing, with metaphors, rhythms, cadences swirling and ringing to a heightened sense of what the complexity of human emotion can sound like if there were words, allusions, similes, and metaphors that could give life and texture for what are, in his plays, inchoate feelings brewing at some base level of the personality before the mind can give them an articulate if flawed rationale.

It was the task of Shakespeare, the poet, and the playwright combined to give verbal music to what were speeches that made private thoughts, half-plotted schemes, inarticulate resentments, paranoia, the whole conflicting brew of insecurity, self-doubt, and malevolence into something that was the equivalent of music, a sweet and stirring sound that bypasses the censoring and sense-making intellect and which makes even the foulest of schemes seem just and only natural. The writing approximates music from the page and provides for a more complicated task when considering our responses to a provocative set of stanzas. Dylan is a songwriter, a distinct art form, and his words are lyrics, which cannot be experienced to their fullest without the music that goes along with them. One may, of course, hum the melodies while pouring over the lyrics and mentally reconstruct of listening to songs of an album, but this proves the point. Of themselves, Dylan's lyrics pale badly compared to page poets. With his music, the lyrics come alive and artful, at their best. They are lyrics, inseparable from their melodies, and not poems, which have another kind of life altogether.

Cohen takes more care in words he selects to tell his tales. He creates his moods, as he provides a sense of location, tone, and philosophical underpinning while also working subtly working to suggest the opposite of whatever mood he might be getting at. Cohen is simply more careful than Dylan.

In word selection, more discriminating; the architecture of literary influence is displayed in the disciplined rhymes of Cohen's parable-themed lyrics, elegantly so. It is, to be sure, a matter of choice how a writer manages their word flow. Cohen's writing has a sense of someone who labors hard to make the image work, to have that image compliment and make enticingly evocative a scenario that starts off simple and then arrives at a moment of fatalistic surrender to powers greater than oneself, both sensual and spiritual. My feeling for Dylan's method is that he is an admirer of what Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac regarded as Spontaneous Bop Prosody, a zen-like approach to an expression where it was regarded that the first thought was the best thought one could have on a subject.

Good poets, great poets, are writers when it gets down to what they do, and it’s my feeling that Cohen’s experience as a novelist, short story writer, and playwright has given him a well-honed instinct for keeping the verbiage to a minimum. This is not to say Cohen is a chintzy minimalist, such as Raymond Carver, or that fewer words in a piece are, by default, superior to longer word counts; rather, Cohen just has a better sense of when it’s time to stop and develop a lyric further.

" It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)"is a terrific, innovative song lyric, and as a lyric does not have the same power as a well-written poem has on the page when that lyric hasn't the music to give it momentum. The power of the lyric has a sustained "oh wow" element, one line after another summarizing the sad state of the Perfect Union, the Idealized world in harsh, ironic terms, each image and beat of the intoned images, critical, lively, surreal in a seamless mash-up of dissimilar concepts, are lifted, foisted, tossed to the listener by the steady and firm strums of the simple guitar Dylan maintains. Lyrics have their advantages and can be quite artful and subtle, but I maintain that they're a different art form; the words are subservient to the song form, where poems of every sort are autonomous, structures made entirely of language. (Unless, of course, you're a Dada poet who just arrived here with a time machine).

There is much quality to the later songs, but they are not among Dylan's greatest as a body of lyrics. Dylan is called more often than not a poet because of the unique genius of his best lyrics; I don't think he's a poet, but a songwriter with an original talent strong enough to change that particular art forever. I do understand, though, why a host of critics through the decades would consider him a poet in the first place. My list is the songs I think that justify any sort of reputation Dylan has a poetic genius. I like most of the songs mentioned above for various reasons other than the ones on my initial 35 choices; the longs there manage an affinity for evoking the ambiguities and sharp perceptions of an acutely aware personality who is using poetic devices to achieve more abstract and suggestive effects and still manage to be wonderfully tuneful. No one else in rock and roll, really, was doing that before Dylan was. On those terms, nothing he's written is quite at the level of where he was with the songs on my list; this list consists of the body of work that substantiates Dylan's claim to genius." Just Like a Woman" is one of the finest character sketches I've ever heard in a song. What's remarkable is the brevity of the whole, how much history is suggested, inferred, insinuated in spare yet arresting imagery. I rather like that Dylan allows the mystery of this character to linger, to not let the fog settle. It is the ambiguity that gives its suggestive power, and there is the whole element of whether the person addressed is a woman at all, but rather a drag queen. It's an open question; it's a brilliant lyric.

...See them big plantations burning

Hear the cracking of the whips

Smell that sweet magnolia blooming

See the ghosts of slavery ships

I can hear them tribes a-moaning

Hear that undertaker’s bell...

Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You can almost think that you’re seein’ double

On a cold, dark night on the Spanish Stairs

Got to hurry on back to my hotel room

Where I’ve got me a date with Botticelli’s niece

She promised that she’d be right there with me

When I paint my masterpiece

Well, I had a feeling that the general good feeling this album conveys is that Dylan wasn't trying too hard to prove he's a genius. The record is straightforward, and the language is remarkably free of affectation, a tendency that has plagued him post-JWH. I especially like "Sign in the Window"; it has the sincerity and actual and momentary acceptance of where one happens to be in a certain part of life and offers a new set of expectations. The perfectly natural language here, good and unexpected rhymes, telling use of local detail that give us color and history without sagging qualifiers to make it more "authentic," the lyrics are a recollection of a trip, of places visited, of perspectives changing, a nice string of incidents in a language that sounds like a real voice telling real things, with genuine bemusement.

Sunday, April 26, 2020

DYLAN GIVES YOU A SEVENTEEN MINUTE SPANKING

This song is a welcome, if sadly belated companion to the Phil Ochs masterpiece The Crucifixion, which is among the best rock-poem lyrics ever scribed and which handily beat Dylan at his own rock-poet game; this is prime Dylan, I believe, older, older, wizened and wiser, but a man aware of his own legacy and reputation as an artist who needs to put life into perspective, the ways in which he emerged after the Fall From Grace, meaning the assassination of JFK and the end of the myth of an American Camelot, a sprawling attempt to reconcile what seemed to be promised by the Presence of John F. Kennedy under who's direction a country could transcend the differences that separate us and have us join together in common cause of a creating a more perfect union and the witnessing and not wholly disguised disgust toward the same culture that, in the current climate, is drunk on personal pronouns and the assumption that gross materialism and mythological entitlements come with the words that refer to oneself as the only agent of action that matters.

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Rolling the stone uphill

Author Greil Marcus made a name as a rock critic by insisting that the tide of history is directly mirrored by the pop music of the period. This can make for exhilarating reading because Marcus is, if nothing else, an elegant stylist given to lyric evocation. But it is that same elegance that disguises the fact that he comes across as a middling Hegelian; the author, amid the declarations about Dylan, the Stones, the Band, and their importance to the spontaneous mass revolts of the sixties, never solidifies his points. He has argued, with occasional lucidity, that the intuitive metaphors of the artist/poet/musician diagnose the ills of the culture better than any bus full of sociologists or philosophers and has intimated further that history is a progression toward a greater day. Marcus suggests through his more ponderous tomes—Lipstick Traces, Invisible Republic, The Dustbin of History—that the arts in general, and rock ‘n’ roll in particular, can direct, in ways of getting to the brighter day, the next stage of our collective being.

Author Greil Marcus made a name as a rock critic by insisting that the tide of history is directly mirrored by the pop music of the period. This can make for exhilarating reading because Marcus is, if nothing else, an elegant stylist given to lyric evocation. But it is that same elegance that disguises the fact that he comes across as a middling Hegelian; the author, amid the declarations about Dylan, the Stones, the Band, and their importance to the spontaneous mass revolts of the sixties, never solidifies his points. He has argued, with occasional lucidity, that the intuitive metaphors of the artist/poet/musician diagnose the ills of the culture better than any bus full of sociologists or philosophers and has intimated further that history is a progression toward a greater day. Marcus suggests through his more ponderous tomes—Lipstick Traces, Invisible Republic, The Dustbin of History—that the arts in general, and rock ‘n’ roll in particular, can direct, in ways of getting to the brighter day, the next stage of our collective being.