(This was an interview I did with the late guitarist in 1974, in a Sunset Strip hotel room in Los Angeles where Coryell and his new band, The Eleventh House, were performing at the legendary Troubadour to support their debut album Introducing the Eleventh House. It's been often said since his passing that Coryell was a very nice guy, a class act, a friendly and amiable sort. Sorry, scandal seekers, no dirt here, as I can attest that the guitarist was absolutely all those things. This piece originally appeared in the San Diego Door).

“John McLaughlin and I shouldn’t be

mentioned in the same sentence,” said jazz guitarist Larry Coryell reacting to

the endless comparisons between him and his British counterpart. Well meaning

comparisons between Mahavishnu Orchestra and Coryell’s new band. The Eleventh

House have been so relentless that a novice listener might

Assume that the veteran musician is

arrive late to the jazz-rock arena. Coryell shrugs and sits back in the chair in his Sunset Strip hotel room where

he’s been resting before that night’s engagement at The Troubadour in Westwood.

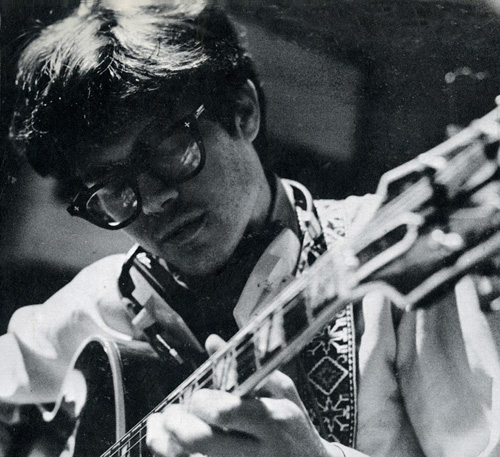

He has an unplugged electric guitar in his hands, his fingers running through a

series of nimble exercises along the frets as he speaks. The guitarist is

emphatic on the distinct nature of the music of the Eleventh House.

“Similarities exist, sure,” he

continues, casually scanning the swimming pool of a Sunset Strip hotel while he

stifled a yawn, “but beyond that, the styles vary vastly. I’m basically a white

rocker caught up in black music. Tm funky, and I like to keep a funky edge to

my playing. McLaughlin hasn’t an ounce of funk in his body. I admire him an

awful lot and we’re good friends, don’t get me wrong. It’s just that I think

the Eleventh House is going places Mahavishnu Orchestra overlooked.”

Larry Coryell is a member of that small

vanguard of jazz musicians to seriously pursued the elusive jazz rock fusion,

the notable others being Miles Davis, Tony Williams, Gary Burton , with whom he

played, and a number of others who broke ranks with tradition. From his days

with the Gary Burton Quartet in the mid-sixties to his own series of erratic

but always boldly experimental albums, Coryell has sought to fuse the hard rock

immediacy to the fleet fingered ecstasy of jazz. Riffs,phrases and whole lines

of blended improvisational strategies that are his creation are only now being

assimilated into the lead guitarist vocabulary.Against the jazzy feel of Lawrence’s

soaring trumpet soliloquies and Mandel’s elegant piano textures is the abrasive

hard rock of Coryell’s guitar. He likes to start playing up the blues end of it

all, then whipping out unexpectedly, some deliciously fast jazz lines. Getting

faster and more complicated as the solo continues, you’re sure his fingers will

burn holes in the guitar neck. His body rocks steadily on the stage, making

faces with each long and mournful sustained note. Not exactly an Alice Cooper

feat of showmanship, but it’s nice to see someone having a good time without

breaking his neck to prove it.

“I’m the luckiest cat in the world,”

said Coryell, “This band is literally bursting with ideas. Our first album was

' only a sampler of what were capable of. Alphonse, he’s got material, Mandel

has material, and I’ve got some. Maybe the next album will be a double record

set. Then we could really stretch out things and give everyone room.” The

album. “Introducing the Eleventh House” on Vanguard has “With Larry Coryell”

emblazoned under the group’s name, a necessary move on the record company’s

part to help sell records. “I’m nore of a leader in name,” clarified Coryell,

“I’m a central point where all this unbelievable energy is organized. Frankly,

these cats are too good for me to have to ^ull any authoritarian trip. If someone

‘messes up, a cold look from me is all the reprimand needed. We communicate

that well. We know exactly what’s on each other’s minds.” “I wish Vanguard

would go out of their way and be a big record company for us,” he laments, revealing

a disdain of corporate meddling.

Larry-Coryell is the first jazz musician

to seriously pursue the elusive jazz/rock fusion

“I listen to young guys like Tommy Bolin

who played on Billy Cobham’s’ album, or Bill Connors from Chick Chorea’s Return

to Forever,” he reflects, “playing licks 1 created back in the mid-sixties, but

adding their own ideas. Man, they turn my head around. I end up taking some of

their things and sneaking it into my own playing.” He eases back in his chair,

rubbing his hand through his lightly greyed black hair and adds, “Man, in a few

years, these guys will burn while I’m playing cocktail jazz.” But in the

meantime, Coryell thinks he’s the best at what he does, and thinks the Eleventh

House is the band to bring the best out of him. Live, the band is a testimonial

to high energy music. As the band assumed the minuscule Troubadour (where

they’d been playing a week long, three show a night gig). Eleventh House’s

technicians didn’t appear much different than the varied roadies who rushed

around trying to shift equipment for each set. But once past the hassles, the

band exploded in an intense kinetic fury. Playing against Coryell’s galvanic

guitar was Mike Lawrence on electric trumpet and Mike Mandel on electric piano

and synthesizer. Bolstered and driven on by the multi handed percussion of

Alphonse Mouzon and Danny Trifan’s agile bass underpinnings, Coryell, Lawrence

and Mandel would play a series of quick and complex melodies, and then spin off

into individual superfast but concise solos. Then, Coryell and Lawrence would

trade fours at breakneck pace while Mandel laced through it all, creating

delicate patterns until the other two muted themselves and let him make a

definite other worldly statement with his synthesizer. becoming known to the

general record buying public. “Selling fifty thousand copies of a jazz album is

respectable, but we want to sell hundreds of thousands of copies. Man, we want

this band-to be known to the world, but for the music, and nothing else. It’s

to our disadvantage, I suppose, that we don’t wear funny clothes, jump around

on stage, or destroy our instruments. We’re naked on stage, there’s nothing

else except the music, and there shouldn’t be. On a good night, we can’t be

touched.”

Scratching his chin, Coryell pushed the

owl framed glasses up the rim of his nose and regretfully added, “The band

sounds tired. We’ve been on tour. 1 wish we could recapture the energy we had

last week at the University of Paris. There, the Eleventh House’s rapid fire

energy was so intense that the rhythm section broke into a musical fight. It

was like going beyond racial, cultural and religious barriers and them saying

to each other ‘All right motherfucker, get down,’ then driving the music to the

wall and then right through it. Alphonse energized everyone, Danny pushed

harder, Mike Lawrence and Mike Mandel and I were trading fours and switching

eights so insanely fast that no one in the band could believe it.” He closed

his eyes and picked off a fast lick on the guitar he’d been toying with. “I

think Tm the luckiest cat in the world to have this group,” he restated as he stood

up and took a long swig from his beer, “The communication is= fantastic.

Basically, let me say, there are only two kinds of music in the world: good and

bad. Eleventh House does the best music in the world.”