A brief piece appears in Slate this week that wonders how smart dance hit phenomenon Lady Gaga happens to be with her conspicuous cherry-picking of style points from previous avant garde trends, with some discussion of the specific debt she might owe to Madonna. The article's theme is that there is a constant recycling of cultural artifacts that , it seems, a few people manage to package and market into lucrative careers, but one might make note a sub theme that goes uncommented upon; the recycling of old feature story ideas.If one were to change names, references and dates, we'd have the same sort of article that appeared , a dozen a month, during the mid-eighties and early nineties that attempted to parse Madonna. What Lady Gaga and Madonna both share is not only pretentiousness but a talent for recycling dated avant-garde gestures and an instinct of what they can get away with in a climate where even the recent past is forgotten. The basic difference between the two, it seems, is that Lady Gaga would really like to be taken seriously , as one can see in her continued references to Warhol, performance art, Bowie, the Bauhaus school.

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

LADY GAGA'S STATUS IN 2009

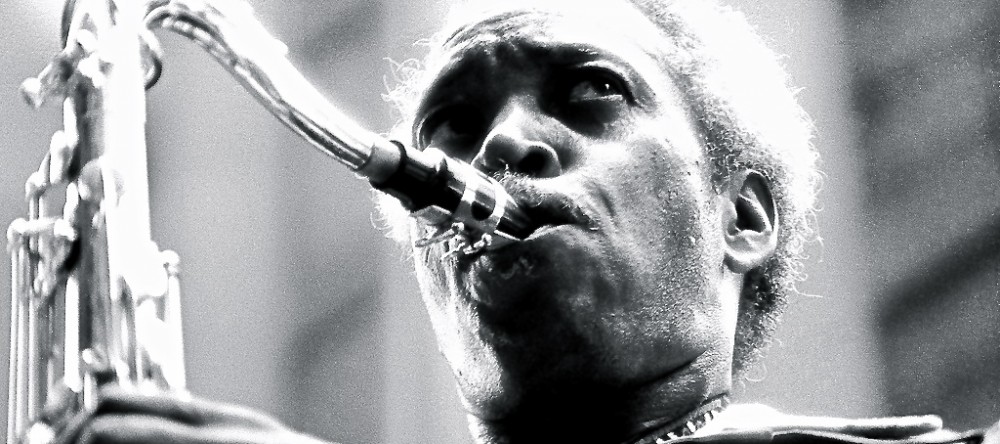

THE FLUIDITY OF SONNY STITT

Monday, July 18, 2022

NICE WORDS FOR THE STANDELLS, AND A FEW FOR THE ELECTRIC PRUNES

Saturday, July 9, 2022

THE BEATLES AS GUITAR HEROES

My view, of course, but I would argue resolutely that the opening of the Beatles 1965 hit "Paperback Writer" is one of the greatest intro guitar figures in rock history. I doubt I'm alone in this view: this tune prefigures a lot of non-metal hard rock that came after it. It's easy enough to imagine Van Halen or Dixie Dregs easily refitting the song for even more guitar slam-dunkery. And beyond the guitar-rock bona fides, it has the additional advantage of being quite literate. McCartney and Lennon are said to have written the lyrics together, and it's remarkable that the subject of the song is a hack writer who maintains he can compose any sort of pulp fiction, on demand, for a fee. I was attracted to it because I was reading numerous novelizations of TV shows and popular films at the time, cheap paperback spinoffs, and I wondered who these folks were that scribed this stuff. I wondered how, in my mid-teens, I could get in on the action.

What I particularly like about how these verses work is that the character is allowed to tell his story. Just the way he describes what he's able or willing to do to get the job reveals a personality in a few deftly stated details. This is much better than, say, "Nowhere Man", an attempt at a "message" song ala Dylan ; I never liked that tune principally it was a ham-handed handed attempt to "tell it like it is". Who the narrator is, certainly not the nowhere man himself, is caustic, critical, judgmental, with none of the faults outlined being convincing in any regard. And the turn around, that little "twist", the "Isn't he a bit like you and me?" line where we learn that we all share the same vanities and inanities of personality, was a hokey, easy and dumb sounding morale of the story as has ever been conceived by major songwriters. "Paperback Writer", though, is a minor masterpiece, and is effective for the same reason an Elmore Leonard crime yarn is: character driven, personality revealed through dialogue, no authorial intrusion instructing a reader (listener) what to think. The song shows, it doesn't tell, and it rocks.

Friday, July 1, 2022

CITY, COUNTRY, CITY: Blues Harmonica and Organ Kick Out Hard Bop Jams!

City, Country, City-- Jason Ricci and Joe Krown

precision of performance, JR's long improvisations are master classes in solo building; he builds mood with a few notes, a partial duplication of the melody, and then ventures forth, filling out the ideas, playing on, before and after the beat in playful investigation, surely moving toward a wondrous and prolonged stretch of cadenzas that deconstructs and reassembles the composition at hand. It's the stuff of wonder to behold Ricci start with bluesy aggression before eventually venturing off in various musical side roads to see if he can produce musical moments no one expected. Classical phrases, jazz chromaticism, fleet bluegrass pentatonics, hard power-trio blitzing, softer, lyric acoustic interludes are the elements this player has mastered, and which give his harmonica power. Jason Ricci, incidentally, played on Johnny Winter's Grammy Award-winning album Stand Back in 2014, was invited by former David Letterman band leader Paul Shaffer to play on "Born In Chicago" for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 2015 (broadcast on HBO), and has released twelve albums with several musical alliances including the scorching New Blood, with singer-songwriter J.J. Appleton, and most recently with the visceral Bad Kind.

JUMP CHILDREN --the Scott Silbert Big Band

Little else existing gets the blood pumping faster than the pulverizing rhythm of big band swing. Limbs twitch, hands beat a tempo on table tops, feet tap then turn and then twist in acrobatic dervishing as the ballroom floor fills with the righteous joy of dancers moving to the galvanizing pace of trombones, trumpets, and saxophones galore joined in a righteous 4/4 stride. In its prime in the 30s, 40s and up to the 50s, it was the music supreme. Ellington, Basie, Goodman, Harry James, the Dorsey brothers, and many others filled the ballrooms, the concert halls, and radio airwaves coast to coast.

It was rebellion, rhythm, pot, secret hooch in pocket flasks, riffs romance, the music of a Nation on the go on the dance floors, in the factories, on the march in the War to End all Wars as America seduced the world with the sweetest sounds this side of heaven. I'm nearly 70, born too early in 1952 to remember what monumental big deal the big bands were, but decades of speaking to elders kind enough to share their memories and record collections with me, I think it would be safe to assume that collectively those telling me tales of big bands, tour buses, and bandstands thought that this was a glorious thing that would never end. But it did. The eventual ascendancy of Elvis, Chuck Berry and rock and roll in general in the 50s, to make a complicated tale too brief in the telling, was a principal reason the Big Bands were pushed from the center spotlight. Though never completely out of the public mind, jazz in general and big band jazz in particular became marginalized. Efforts over the years to restart interest in the Swing Era brand of brassy sass have mixed results over the years. In a general way and in the interest of keeping this review concise, suffice it to say that college big bands, various sorts of revivalist ensembles and especially that faddish "Swing Revival" of the late eighties-early 90s, to varying degrees, struck me as academic recreations at best, gimmicky opportunism at worst. You couldn't help but wonder if anyone would happen along, unexpected, with a blazing take on this grand tradition, not as an ancient thing that needed to be refurbished or rehabilitated instead as a life force that can make the nervous system jump again in an age where modern music seems determined to deaden our wits.

Jump Children by the Jeff Silbert Big Band is a choice step in that direction, a session of hard-rocking swing music, fueled by propulsive drums, two fisted piano chords and sharp, superbly textured, rapidly applied horn and reed arrangements. Silbert, a jaunty and fluid tenor saxophonist and arranger and a member of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, proceeds here as though Big Bands never went out of style. He's assembled a formidable fourteen-member band, players who lock together in common cause to move the listener through deep, brash colors, and intricate time signatures. There's abundance of ensemble electricity here. Or, more like an embarrassment of hot, very hot jazz.

A bold statement, but the music's galloping swagger is evidence that enthralls and rattle the senses. The album opener and title track "Jump Children", a tune recorded in 1945 by the International Sweethearts of Rhythm (an all-women and integrated unit that found a measure of international acclaim) is given a blasting, endearingly fidgety treatment here, with fine solos from trumpeter Josh Kauffman on trumpet and Grant Langford on tenor sax swiftly and lightly darting over and around the cut time horn arrangements, all of which boosts Gretchen Midgely's already animated vocals to heights of finger snapping jive. This collective of virtuosos through a rich swath of known and less known tunes from the period, performed with a superb rhythm section that makes the music move with a youthful flair you might not have expected. There is nothing dated here. There are many sweet spots, but I would point out two especially catchy numbers, the first being an intrepid iteration of 1939's "In a Persian Market" by Larry Clinton indulges in magnificent stop-time fun after the main theme is stated. Second, the Silbert Big Band's treatment of Mercer Ellington's "Jumpin' Punkin" from 1941 is an elegant jaunt, a spare set of horn charts laced together with sublime statements from multi-reedist on clarinet and Leigh Pilzer on baritone sax. The album concludes on a stratospheric note, the warhorse tune "Stompin at the Savoy" (composed by Chick Webb and Edgar Samson), the trademarked horn charts soaring over a brutally effective swing section while a round house of soaring and succinct solos from Kauffman (trumpet), Jen Krupa (trombone), Silbert (tenor sax) and Ken Kimrey switch off with the unison horn lines in a melee of musical chatter.