I like loud and distorted guitar the old school way, in the form of jamming power trios, those guitar-bass-drums shoot outs where the downbeats started at debated counts and the length of improvised middle section was undetermined and unpredictable. Improvisation, riffing, vamping, monochromatic chord mongering, the center portions of this species of spontaneous noise took a style cue from several generations of black American blues geniuses and took their clear, elegantly expressed formulations of anger, pain , dread and joy and tweaked the pentatonic elements to a narrowed strain of white male rage, performed at volume levels beyond endurance levels , with the nimble, simple, eloquent rhythms and solo configurations of guitar , harmonica, banjo being replaced with a waves of distorted notes bent to their furthermost pitch of emotional credibility. It was perfect for the smoky ballrooms I went to in the late '60s, where the likes of Cream, Blue Cheer, Sir Lord Baltimore, T.Rex and Mountain belched, groaned and assaulted a beleaguered audience of addled brains with their instrumental abuse; on some nights the commotion and clamor reminded you more of a demolition derby instead of a unique engagement with a fleeting muse. The impact was more important than configuration. There was joy when, in Detroit where I lived, I came upon the MC5 and the Stooges. The 5 were every car Detroit had manufactured being tossed off the top of the Penobscot, the tallest building in town; they had a speed and power only the fury of an accumulating gravity could provide, and half the fun of watching these guys batter, abuse and flail their instruments while the wiggled and wrenched themselves in hip-thrusting deliriums was the expectation of their metaphorical car crashing, smashing into the hard, metal strewn concrete below. The Stooges were, on the other hand, the guitar that was tossed off with a violent fling at a bad rehearsal and left on, still plugged into the amp, humming and crackling the whole night; Ron Ashton's guitar work was perfect, imperfect, with a wood-chipper rhythm, a perfect three and two-chord background for Iggy Pop, who's psycho-sexual explorations into the outer areas of teenage impatience would make you think of a zombies severed arm. It still twitches across the blood, the hand is still making grasping motions for your neck, you realize that even death cannot stop this force that requires your attention.

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Saturday, February 16, 2019

NO FUN WAS OUR FUN

Monday, February 11, 2019

OOPHA!

Rock and roll is all about professionalism , which is to say that some of the alienated and consequently alienating species trying to make their way in the world subsisting on the seeming authenticity of their anger, ire and anxiety has to make sure that they take care of their talent, respect their audience's expectations even as they try to make the curdled masses learn something new, and to makes sure that what they are writing about /singing about/yammering about is framed in choice riffs and frenzied backbeat. It is always about professionalism; the MC5 used to have manager John Sinclair, the story goes, turn off the power in the middle of one of their teen club gigs in Detroit to make it seem that the Man was trying to shut down their revolutionary oooopha. The 5 would get the crowd into a frenzy, making noise on the dark stage until the crowd was in a sufficient ranting lather. At that point, Sinclair would switch the power back on and the band would continue, praising the crowd for sticking it to the Pigs. This was pure show business, not actual revolutionary fervor inspired by acne scars and blue balls; I would dare say that it had its own bizarre integrity, and was legitimate on terms we are too embarrassed to discuss. In a way, one needs to admire bands like the Stones or Aerosmith for remembering what it was that excited them when they were younger, and what kept their fan base loyal.

Rock and roll is all about professionalism , which is to say that some of the alienated and consequently alienating species trying to make their way in the world subsisting on the seeming authenticity of their anger, ire and anxiety has to make sure that they take care of their talent, respect their audience's expectations even as they try to make the curdled masses learn something new, and to makes sure that what they are writing about /singing about/yammering about is framed in choice riffs and frenzied backbeat. It is always about professionalism; the MC5 used to have manager John Sinclair, the story goes, turn off the power in the middle of one of their teen club gigs in Detroit to make it seem that the Man was trying to shut down their revolutionary oooopha. The 5 would get the crowd into a frenzy, making noise on the dark stage until the crowd was in a sufficient ranting lather. At that point, Sinclair would switch the power back on and the band would continue, praising the crowd for sticking it to the Pigs. This was pure show business, not actual revolutionary fervor inspired by acne scars and blue balls; I would dare say that it had its own bizarre integrity, and was legitimate on terms we are too embarrassed to discuss. In a way, one needs to admire bands like the Stones or Aerosmith for remembering what it was that excited them when they were younger, and what kept their fan base loyal.

It’s not a matter of rock and roll ceasing to be an authentic trumpet of the troubled young soul once it became a brand; rather, rock and roll has always been a brand once white producers, record company owners and music publishers got a hold of it early on and geared a greatly tamed version of it to a wide and profitable audience of white teenagers. In any event, whether most of the music being made by Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and others was a weaker version of what was done originally by Howlin Wolf, Muddy Waters et al is beside the point. It coalesced, all the same, into a style that perfectly framed an attitude of restlessness among mostly middle-class white teenagers who were excited by the sheer exotica, daring and the sense of the verboten the music radiated. It got named, it got classified, the conventions of its style were defined, and over time , through both record company hype and the endless stream of Consciousness that most white rock critics produced, rock and roll became a brand. It was always a brand once it was removed from the black communities and poor Southern white districts from which it originated. I have no doubt that the artist’s intention, in the intervening years, was to produce a revolution in the conscious of their time with the music they wrote and performed, but the decision to be a musician was a career choice at the most rudimentary level, a means to make a living or, better yet , to get rich. It is that rare to a non-existent musician who prefers to remain true to whatever vaporous sense of integrity and poor. Even Chuck Berry, in my opinion, the most important singer-songwriter musician to work in rock and roll — Berry, I believe, created the template with which all other rock and rollers made their careers in music — has described his songwriting style as geared for young white audiences. Berry was a man raised on the music of Ellington and Louie Jardin, strictly old school stuff, and who considered himself a contemporary of Muddy Waters, but he was also an An entrepreneur as well as an artist.

He was a working artist who rethought his brand and created a new one; he created something wholly new, a combination of rhythm and blues, country guitar phrasing and narratives that wittily, cleverly, indelibly spoke to a collective experience that had not been previously served. Critics and historians have been correct in callings this music Revolutionary, in that it changed the course of music, but it was also a Career change. All this, though, does not make what the power of Berry’s music — or the music of Dylan, Beatles, Stones, MC5, Bruce or The High Fiving White Guys — false, dishonest, sans value altogether. What I concern myself with is how well the musicians are writing, playing, singing on their albums, with whether they are inspired, being fair to middlin’, or seem out of ideas, out of breath; it is a useless and vain activity to judge musicians, or whole genres of music by how well they/it align themselves with a metaphysical standard of genuine, real, vital art making. That standard is unknowable and those putting themselves of pretending they know what it is are improvising at best. This is not a coherent way to enjoy music. One is assuming that one does, or at one time did, enjoy music.

All entrepreneurs are risk takers, for that matters, so that remains a distinction without a difference. What matters are the products — sorry, even art pieces, visual, musical, dramatic, poetic, are “product” in the strictest sense of the word — from the artists successful in what they set out to do. The results are subjective, of course, but art is nothing else than means to provoke a response, gentle or strongly and all grades in between, and critics are useful in that they can make the discussion of artistic efforts interesting. The only criticism that interests are responses from reviewers that are more than consumer guides — criticism, on its own terms in within its limits, can be as brilliant and enthralling as the art itself. And like the art itself, it can also be dull, boring, stupid, pedestrian. The quality of the critics vary; their function in relation to art, however, is valid. It is a legitimate enterprise. Otherwise, we’d be treating artists like they were priests. God forbid.

Sunday, February 10, 2019

TOM JONES GIVES CSNY A SINGING LESSON

I saw this when it was first broadcast and thought even then that it was an inspired mismatch of musical sensibilities. Jones is one of the greatest white rhythm and blues singers of all time--range, power, nuance, texture echo Otis Redding, Ray Charles and Solomon Burke with stunning ease and feeling--but he is incapable of just standing still and singing the notes. He oversings this tune--too much melisma on a song requiring a less protective approach is melodramatic, not dramatic, and can seem silly although it is fun to hear Jones give an overwrought reading of the warning that the listener ought to be ready to cut their hair should things get hairy with the Man. A relisten, however, shows the world what should have been obvious to me when I was young, that what Jones has as a voice is truly magnificent, a masculine --not macho--baritone, with range, texture, strength of tone that does not falter on the high notes nor strains nor gargles for grit when navigating the bottom register. And what he has in the center of that voice is pure magic so far as a natural affinity to African American vocal stylizations. Jones may be investing this Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young song with more emotional firepower than subject or melody actually need, but it's exciting to witness Jones shoot off fireworks while never quite making the boat capsize or sink. His swooping melismas, his growls, his insertions of gospel-inspired ad-libs and Wilson Pickett grunts and varied exclamations rather compliments what is already a rare occurrence in what amounts to an inane bit of rock and roll history, that CSN and Y actually sound like a band instead of a group of bad actors sullenly fulfilling the terms of the fine print. The reedy harmonies of Graham Nash and Neil Young and the smirking David Crosby give a strange, oddly affecting folk-mass solemnity to Jones' artful bellicosity, and even Steve Stills' stabs at competing with Jones with his addition of soul-inspired call-and-response can't spoil a perfect television moment. The swinging, swank, tight slacks wearing Jones, that guy who has to keep that pelvis in motion regardless of subject matter, mood or prevailing fashion and decor, get down with The People! Odder things have been aligned, I guess, but not many. Interesting band reactions as well; David Crosby looks amused and looks to be suppressing a snicker, while Stills sounds inspired by Jones' gospel inclinations to be a soul man himself. Neil Young appears thoroughly unamused.i'm not usually interested in specialty albums, the kind of thing that has Rod Stewart singing the Great American Songbook, but I always hoped that Jones would record and release an album of rhythm and blues classics, with select obscurities thrown in. It would have been a transcendent moment, where this white guy from Wales steps away from the Vegas glitter dome and unleash that magnificently authentic voice on the range of songs it was seemingly intended for. There is something of a freak show about Jones, but that was all stage presence, details rehearsed for the spotlight and the cameras. An album might have made listeners forget the absurd trappings surrounding Jones in the media and concentrate on the bed rock emotion of the songs and the voice that would rasp, wail and soar on their emotional core. That would have been a cool thing. Such moments, though, are the stuff of the perfect world that somehow eluded us.

Friend, writer Barry Alfonso offers this:

Thanks for posting this GREAT clip, Ted. It’s just about the best one of CSN&Y I’ve ever seen – for once, their performance as a band seems unified and dynamic, rather than a lapful of undigested egotism. And thanks also for initiating a critical conversation about Tom Jones, a hard-to-place figure on the pop landscape who nevertheless made some wonderful and memorable singles back in the day. What’s amazing about Jones is that his florid amalgam of R&B and Vegas was so sturdy and adaptable, as well as the fact that his souped-up lothario persona could seem cartoonish and exciting at the same time. I wonder why it was so essential to Jones to choose goofily melodramatic material that bordered on pure cheese: “It’s Not Unusual,” “What’s New Pussycat,” “Help Yourself,” “Delilah,” “She’s a Lady,” etc. In the hands of anyone else, these crass ditties would seem totally stupid, a parody of leering lounge-smarm. But Jones had the chops and the charisma to make them fun and triumphant. It was a kind of genius, a unique one at that.

Friend, writer Barry Alfonso offers this:

Thanks for posting this GREAT clip, Ted. It’s just about the best one of CSN&Y I’ve ever seen – for once, their performance as a band seems unified and dynamic, rather than a lapful of undigested egotism. And thanks also for initiating a critical conversation about Tom Jones, a hard-to-place figure on the pop landscape who nevertheless made some wonderful and memorable singles back in the day. What’s amazing about Jones is that his florid amalgam of R&B and Vegas was so sturdy and adaptable, as well as the fact that his souped-up lothario persona could seem cartoonish and exciting at the same time. I wonder why it was so essential to Jones to choose goofily melodramatic material that bordered on pure cheese: “It’s Not Unusual,” “What’s New Pussycat,” “Help Yourself,” “Delilah,” “She’s a Lady,” etc. In the hands of anyone else, these crass ditties would seem totally stupid, a parody of leering lounge-smarm. But Jones had the chops and the charisma to make them fun and triumphant. It was a kind of genius, a unique one at that.

Saturday, February 9, 2019

|

| MUDDY WATERS' Woodstock ABLUM --| Muddy Waters and Friends |

I spent dozens of hours breaking down and learning his harmonica work on "Broke My Baby's Heart" and "New Walking Blues". Wonderful, wonderful blues playing, with perhaps the best band he ever formed. If you haven't already, check out the obscure Muddy Waters Woodstock Album. The album is a revelation, as it has Waters stepping a few steps back from the rocking, Chicago style backbeat, raw and blistering in a fashion only genius can achieve, and here taking up a swing upbeat. Save for the rumblings of Waters' voice, always a place of deep echo and lean-close innuendo, some of these tracks would fit in well with the suited urbanity of B.B.King. It is a gem alright, a rousing, spirited transitional session placing Waters beyond his stylistic comfort zone. But not too far. Pinetop Perkins provides a bright piano throughout, and former Band utility musician Garth Hudson is a triple threat here on organ, saxophone, and accordion; his accordion work, surprisingly, is a wonderful blues instrument, as can be heard on the sturdy workouts on "Going Down to Main Street", "Caldonia".Whatever jokes the instrument and it's players have suffered at the hands of one comedian over the decades abates somewhat with Hudson's finely fingered boogie and sparkling fills. What caught my ear was the harmonica playing of the late Paul Butterfield; perhaps among the handful of truly important blues harpists, his playing here equals his best efforts. Punchy, fleet, gutty and clean in the same breath, Butterfield demonstrates his mastery of tone and phrase, combining moaning raunch and inspiring single-note runs for maximum effect. Butterfield fans ought to acquire this disc straight away; it's an essential addition to your harmonica player collection. This is a terrific addition to his previous collaboration with Waters, the stomping Fathers, and Sons. For Waters, he is relaxed, at ease, in full command of his singularly masterful voice; within that limited range he can raise the voice to its breaking point, emphasizing a point, highlighting a hurt, suggesting a rebellion against what brings him down, and then slide to the lowest corner of his range and provide the gritty realism that is his hallmark as a blues artist. One is also served a generous portion of Waters' slide guitar work, a perfect compliment to Bob Margolin's stinging bends and blurs; Waters touch is sure and spare, producing a thin, nervous, clear line. It is a wonderful texture in a full-bodied, hard-swinging band. A battler, a lover, a philosopher of the hard road, never with self-pity, never without it.

Friday, February 8, 2019

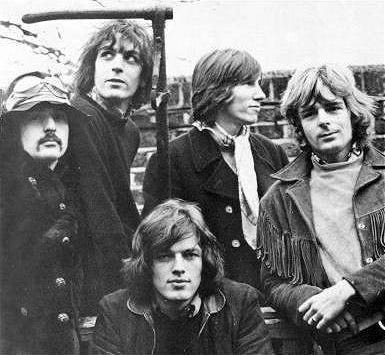

PINK FLOYD'S BEAUTIFUL SLOG THROUGH THE 20TH CENTURY

Rolling Stone has informed us that Pink Floyd, in order to celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the release of their admittedly brilliant album “Dark Side of the Moon”, has invited fans to tune to their website this Sunday, March 24, in order to stream the record, in full. I can’t help but think this is less the gift to fans than the band might think, since any committed fan of Pink Floyd likely already owns the album and has been listened to it relentlessly for decades; myself, I know precisely where every pop, skip and hiss occurs on my long lost vinyl copy. All told, this is one of those records that has been around for so long and has been played so often that I wish I could condemn it as nostalgia, but I can’t. It is a brooding, moody, poetic and richly textured end-of -a the-dream concept album, a masterpiece of disillusion that rivals, I declare, TS Eliot and his beautifully distraught “The Wasteland”.There is in both the mesmerizing defeatism of their respective projects; the shoulder-shrugging and firm embrace of the will to live fully have never found better, more seductive expression, both poem, and album. Refreshing in the music and lyrics of Pink Floyd, as well, was a what I think is unmistakable for the working class; along among British Art Rockers, PF avoided verbal drag and double talking allusions and planted their narrations dead center in a streaming disgust with the mess men have made of the world; politicians and corporations for being such greedy, short-sighted exponents of the profit motive and the misery index, and the common people, for believing lies told them and willfully buying into a fantasy that will only kill them all, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. “Dark Side of the Moon” and “Wish You Were Here” were two endearingly burnished sides of the same dented coin, legitimate and remarkable expressions of a lightly toxic world view.Predictably, with commercial artists contractually obliged to produce new work on a corporation’s schedule, they ran out of fresh things to say; later records tended to be as dreary as dour music is supposed to be. England has a tradition of hippie art-rockers going sour as they edge into their thirties; Barrett had the good sense to just break down and allow his legend to simmer on low boil for decades. It is an accomplishment that he has managed to be that footnote in the Pink Floyd saga that ABSOLUTELY NO ONE FAILS TO MENTION. I like that he his name persists on the band’s name and legend with no effort on his part. His actual story is sad, though, and he would be the first example I would cite when arguing that drug taking without medical need is intellectually indefensible. Waters, though, stuck around, had his moment of glory in which truly great work was done, but he became a boring old cynic bemoaning variations of a faceless, grey, corporate England divorced from a romantically envisioned past. He reminds you of that great sex you had after a cocktail party where you fucked the fried liver out of your partner and then waking up and seeing who it was you were putting it to, or who was placing it in your personhood. Ugly recrimination followed rapidly and you wonder what was worth this current cramping of one’s expressive style. Roger Waters never sang about that. Pink Floyd could have used more Tom Waits and Beefheart and less Basil Bunting.Although I am sick unto death of ever hearing this album again, “Dark Side of the Moon” is a keen and sufficiently angsty expression of a generation’s loss of idealism. Their narcoleptic music and vaguely saddened ruminations, in fact, are an extended impression of a very bad drug crash, when the good vibes of acid and pot became overwhelmed by the critical burn-through of methamphetamines. The irony is that for a band that has lampooned, bemoaned and besmirched regimentation with their mirthless minimalism, their goal, with the live streaming, is to get the last three citizens of the planet who haven’t purchased the disc to buy it, finally, and to become a nonconformist just as the rest of us have always been. Like-minded free thinkers.

DIONNE WARWICK AND GENE PITNEY

I always thought Dionne Warwick was a vocal original. The going tradition for black pop and soul singers had been a very gospel, shout to the rafters approach that required range and training. Warwick had the training, obviously, but not the vocal range and managed in working spectacularly well within her limits. She had an interesting, offbeat sense of when to sing a lyric, a subtle tone of sadness in the lower register, there was a magical sense of her speaking to you directly, softly, after a good cry. This is shown in the video of Walk on By , a song that begins that begins with the pacing of someone trying to hurry down a street, trying to avoid eye contact with a former lover they can't bring themselves to see, a perfect mood, at the edge of the frantic, as Warwick movingly, slowly sings the opening words of her imagined speech to her ex-paramour :

If you see me walkin' down the street

And I start to cry each time we meet

Walk on by, walk on byMake believe that you don't see the tears

Just let me grieve in private 'cause each time I see

I break down and cry, I cryWalk on by, don't stop

Walk on by, don't stop

Walk on by

This is one of the great heartbreak songs of the era, and it shows Warwick's particular genius for softly dramatizing a lyric by underplaying the emotion. Leslie Gore, Patty Duke, and a myriad other pop proto-divas would have raised the roof beams with this song, but Ms. Dionne finds the right pitch. The sorrow, the self-pity, the resignation is all there, but it the quality of Warwick's singing places her not in a sort of hysterical moment of solipsistic self-pity but someone, actually, he is more the Hemingway stoic, shouldering the pain and the grief and dealing with what the everyday life demands. Of course, there is that sweetly sad piano figure in the chorus that presents an effective change in tempo and mood, a circling keyboard figure that halts the forward motion of the narrative and stops the narrator, our singer Dionne, dead in her tracks, briefly and sharply remembering the pain of breaking up.

These are rare and beautiful attributes in a singer, the capacity to emote in such a small scale; she was the exact opposite of the late Gene Pitney, who turned every sad song into an aria of teen heartache. Both singers, incidentally, were blessed to have sung many songs by the Bacharach/David team, two men who knew how to write songs for a singer's vocal strengths.

Bear in mind, I was a big fan of Pitney's. For comparison, above is Pitney singing "I'm Gonna Be Strong", written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil (later covered by Cyndi Lauper in her early band Blue Ash). An extreme bit of heartache here, with the perfect singer for the sad tale. The tempo is the same throughout, but as it progresses, subtly but quickly, Pitney's voice is stronger, filled with more self-aggrandizing emotion, a man turning in his sleep and trying to burn his way through his lose with nothing but stoicism, but who, in the final hour, alone, will just weep as hard and as loud as he is able. The way Pitney's voice climbs to his highest register is chilling, equaling the grandiose swell of the orchestration.

Tortured high notes were precisely what Pitney's music was about, observable in the operatic, compressed, grandiose and florid teen angst songs he sang with a voice that could start out low, smooth, slightly scratchy with restraint, and then in the sudden turn in tempo and a light flourish of horns or sweeping, storm-bringing violins, slide up the banister to the next landing and again defy gravity to the yet the next level as he his voice climbed in register, piercing the heart with melodrama and perfect pitch as the banalest love stories became the raging of simultaneous tempests. It was corny on the face of it, but Pitney had the voice and he had the songs to pull it off and make records that still have that stirring hard-hitting effect; "Town Without Pity", "It Hurts To Be In Love", "Twenty Four Hours to Tulsa", "I'm Gonna Be Strong", and a substantial string of other hits he had ( 16 top twenty hits between 1961 through 1968) took the tearjerker to the next level. As mentioned by someone the other day in the British press commemorating his music, his tunes weren't loved songs, they were suicide notes. Pitney's multi-octave sobbing qualified as Johnny Ray turning into the Hulk wherein the sadder he was made, the stronger his voice became. All this was enough for me to buy his records in the early Sixties when I was just making my way to developing my own tastes in musicians and their sounds.

Most of the early stuff I liked--The Four Seasons, Peter Paul and Mary--I dismiss as charming indulgences of a young boy who hadn't yet become a snob, but Pitney? I kept a soft spot for his recordings in my heart and defended him in recent years when those verbal battles about musical tastes found his name impugned in my presence. The Prince of Perfect Pitch deserves respect for turning the roiling moodiness of teenage love into

sublime expressions of virtuoso emotionalism.

Most of the early stuff I liked--The Four Seasons, Peter Paul and Mary--I dismiss as charming indulgences of a young boy who hadn't yet become a snob, but Pitney? I kept a soft spot for his recordings in my heart and defended him in recent years when those verbal battles about musical tastes found his name impugned in my presence. The Prince of Perfect Pitch deserves respect for turning the roiling moodiness of teenage love into

sublime expressions of virtuoso emotionalism.

DONOVAN WAS GREAT, DONOVAN WAS GREAT

"Sunny Goodge Street" is a panorama, obviously, of a particular urban hip scene so commonly portrayed in flashy and groovy terms in the 60s, but Donovan's version of it makes it seem unpredictable, violent, utterly paranoid and incoherent. It is closer to Burroughs than to Scott McKenzie's saccharine rendering of John Phillip's saccharine to hippiedom "San Francisco (Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair"). Donovan seemed to understand that the counterculture was as much as a creep scene as it was a gathering moment for truth seekers, poets and sincere sensualists who desire both sex and innocence. While the cost of attaining the sorts of forbidden knowledge drugs and the attending hype was unknown, Donovan, last named Leitch by the way, had a foreboding that was rarely expressed by a generation of musicians that was fatally self-infatuated.

"Epistle to Dippy" is nothing less than a direct address of a try-anything scene maker who dashes from drug to scene to fad in an irrational attempt to oust run their own vacuity, their utter lack of soul or genuine sensibility. This is as acidic a portrayal of the poseur as has been written, more potent than the Beatles' politely poo-poohing tune along the same theme, "Nowhere Man". The difference is that D.Leitch is in the trenches, an intrepid reporter perhaps, a Norman Mailer who dared to take the same drugs as those he observed and had enough wits afterward to recall the excruciating banality of a prismatic perspective.

"Young Girl Blues", in turn, is marvelously turned by Marianne Faithful into a bittersweet recollection of an ingenue who had gotten tired of her own hipness and the chronic scene-making; the lyrics are an acute portrait the raging banality of such an ostentatiously noisy and hip scene. Donovan senses, I think, the isolation none of the scene makers can break away from or cure with brand names, loud music, and chemicals. A fair amount of his songwriting holds up, I think, and it holds up for the same reason Norman Mailer's "Armies of the Night" or Tom Wolfe's "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" hold up; they are all , in their own respective ways, exquisitely etched portraits of the Sixties that bypassed the mass-mediated brainwashing fostered by Time and Life magazines and presented the whole notion of Youth Culture and revolution as something that was no less problematic than the Establishment that the ragtag gaggle of miscreants, socialists, opportunistic gurus, draft dodgers, ersatz feminists and the usual assortment of authentic bums and layabouts claimed needed to be changed. Details, blisters, resentment, a sharpened sense for sensing out the fake, the harmful, the mendacious.

What all this means, I suppose, is that it may be time for a major consideration of this man's work, from his days as an obvious albeit inspired Dylan imitator with "Catch the Wind" to becoming something significantly worthy of note during that rich period of the Sixties, a poet/lyricist with a genuine sense of how to compress complex situations, competing sensations and ambivalence (the urge to engage the world as it unfolds coupled with an equal instinct to distance oneself from it) into brief couplets, resonating, terse lyrics and fascinatingly fractured imagery; this was like nothing less than hearing lyrics by T.S.Eliot had the banker scrambled his dueling attraction/repulsion with quality doses of LSD. What Donovon offered the world, one might say, for that brief sliver of time when the pen did not fail him, was a Wasteland where flowers could still grow through the debris of the ruined streets. In this world , though, the flowers were strange, menacing, something we haven't seen before.

What all this means, I suppose, is that it may be time for a major consideration of this man's work, from his days as an obvious albeit inspired Dylan imitator with "Catch the Wind" to becoming something significantly worthy of note during that rich period of the Sixties, a poet/lyricist with a genuine sense of how to compress complex situations, competing sensations and ambivalence (the urge to engage the world as it unfolds coupled with an equal instinct to distance oneself from it) into brief couplets, resonating, terse lyrics and fascinatingly fractured imagery; this was like nothing less than hearing lyrics by T.S.Eliot had the banker scrambled his dueling attraction/repulsion with quality doses of LSD. What Donovon offered the world, one might say, for that brief sliver of time when the pen did not fail him, was a Wasteland where flowers could still grow through the debris of the ruined streets. In this world , though, the flowers were strange, menacing, something we haven't seen before.

Thursday, February 7, 2019

FIRST KILL ALL THE ROCK CRTICS

I gave up hope for rock criticism developing into a respectable form of criticism when I realized that it was, for the most part, a pissing contest for most of the guys who decided to try their hand at it. For every Bangs and Young, there were dozens of lesser lights who proved, at length, that they could make noise aplenty but offer little or no light on the subject. Much of it has to do with how well the current state of the music happens to be, of course, but pop music criticism did come to the point where everyone was recycling what everyone had already written, and the two trajectories being offered readers by the end of the seventies was incomprehensible Greil Marcus/Dave Marsh obscurantism, which insisted that the music they listened to in college dorms was the Spenglarian peak of civilization and that every note played afterward was an inferior facsimile of the authentic, or the knee jerk Bangs imitations where wave after wave of typing nitwits missed out on Lester's capacity for feeling deep emotion and his brand of self-criticism and instead freight us with jabbering sarcasm by the carload. Jim DeRogatis , rock critic for various outlets , author of the Lester Bangs biography "Let It Blurt", rounded up a slew of younger, Generation X pop writers and invited them to select a classic rock album, an album, by consensus, considered to be Canonical and there for inarguably great and then to debunk an older generation of critics' claim for the lasting greatness of those records. It's an interesting idea, I admit, but the result, an anthology called "Kill Your Idols" is a miserably strident, one-note mass of pages dedicated to puerile dismissals of a lot of good, honest music. "Snotty" doesn't do that particular disaster justice.

The problem with the generation of rock critics who followed the late Lester Bangs was that too many of them were attempting to duplicate Bangs' signature and singular ability to write movingly about why rock and roll stars make terrible heroes. Like many of us, Bangs became disillusioned with rock and roll when he discovered that those he admired and was obsessed by--Lou Reed, Miles Davis, and Black Sabbath--were not saints. The discovery of their clay feet, their egos and the realization that rock and roll culture was a thick cluster of bullshit and pretentiousness didn't stymie Bangs' writing. It, in fact, was the basis of Bangs transcending his own limits and finding something new to consider in this. Sadly, he died before he could enter another great period of prose writing. "Kill Your Idols", edited by Jim DeRogatis, is an anthology that is intended, I suspect to be the Ant- "Stranded", the Greil Marcus edited collection where he commissioned a number of leading pop music writers and asked them to write at length about what one rock and roll album they would want to be left on a desert island with; it's not a perfect record--then New York Times rock critic John Rockwell chose "Back in the USA" by Linda Ronstadt and couldn't mount a persuasive defense of the disc--but it did contain a masterpiece by Bangs, his write up of Van Morrison's album "Astral Weeks". His reading of the tune "Madame George" is a staggering example of lyric empathy, a truly heroic form of criticism. "Kill Your Idols", in reverse emulation, assigns a group of younger reviewers who are tasked with debunking the sacred cows of the rock and roll generation before them; we have, in effect, pages full of deadening sarcasm from a crew who show none of the humor or sympathy that were Bangs best qualities. Bangs, of course, was smart enough not to take himself too seriously; he knew he was as absurd as the musicians he scrutinized.

"Kill Your Idols" seemed like a good idea when I bought the book, offering up the chance for a younger set of rock critics to give a counter argument to the well-made assertions of the essayists from the early Rolling Stone/Crawdaddy/Village Voice days who are finely tuned critiques gave us what we consider now to be the Rock Canon. The problem, though, is that editor Jim Derogatis didn't have that in mind when he gathered up this assortment of Angry Young Critics and changed them with disassembling the likes of Pink Floyd, The Beatles, the MC5; countering a well phrased and keenly argued position requires an equally well phrased alternative view and one may go so far as to suggest the fresher viewpoint needs to be keener, finer, sharper. Derogatis, pop and rock music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, author of the estimable Lester Bangs biography Let It Blurt, had worked years ago as record review editor of Rolling Stone and found himself getting fired when he couldn't abide by publisher Jan Wenner's policy of not giving unfavorable reviews to his favorite musicians.

His resentment toward Wenner and Rolling Stone's institutional claims of being a power broker as far as rock band reputations were concerned is understandable, but his motivation is more payback than a substantial refutation of conventional wisdom. The Angry Young Critics were too fast out of the starting gate and in collective haste to bring down the walls of the Rock Establishment wind up being less the Buckley or the Vidal piercing pomposity and pretension than, say, a pack of small yapping dogs barking at anything passing by the back yard fence. The likes of Christgau, Marcus, and Marsh provoke you easily enough to formulate responses of your own, but none of the reviews have the makings of being set aside as a classic of a landmark debunking; there is not a choice paragraph or phrase one comes away with.

Even on albums that I think are over-rated, such as John Lennon's Double Fantasy, you think they're hedging their bets; a writer wanting to bring Lennon's post-Beatles reputation down a notch would have selected the iconic primal scream album Plastic Ono Band (to slice and dice. But the writers here never bite off more than they can chew; sarcasm, confessions of boredom and flagging attempts at devil's advocacy make this a noisy, nitpicky book whose conceit at offering another view of Rock and Roll legacy contains the sort of hubris these guys and gals claim sickens them. This is a collection of useless nastiness, a knee jerk contrarianism of the sort that one overhears in bookstores between knuckle dragging dilettantes who cannot stand being alive if they can't hear themselves bray. Yes, "Kill Your Idols" is that annoying, an irritation made worse but what could have been a fine idea.

Sunday, February 3, 2019

NO ONE WEARS WHITE FACE

As to the matter as to whether Bruno Mars , who is not black, is appropriating black music and an aesthetic born of African American experience, created by talented black artists, well…I don’t know the man’s music, let alone his version of Black Style. I will him be and not mention him again in this harangue. Appropriation has been with us forever, although I would suggest that the non-black musicians playing music that is African American in origin have, for the most part, a genuine love of the sounds they've been exposed to. Theft is theft and black creators must be located, credited and their families paid for the use of the bodies of work that formed the foundation for a huge amount of American culture and a character, but at the same time it seems reductive and ironically bigoted to suggest that only black musicians have the right, let alone the sole ability to make authentic jazz, blues, or rhythm and blues. Forcing matters of creativity into a any kind of requirements for acceptance is absurd and contrary to what art is supposed to do, the process through which an individual--an artist--experiences the world and , through the use of whatever medium moves him enough to create objects of beauty of contemplation that hadn't existed before. Pretty much going with Marcuse on this one, as in his bookd the Aesthetic Dimension, where he argues that Society, The Establishment, the Powers that Be, need to leave the artists and allow them to perform their task with their art making, to produce joy. Otherwise, if held to aesthetic principles that are contrary to inspiration, it ceases to be art. It is Propaganda. We do not need an American version of Soviet Realism, no matter where it comes from. It goes to authenticity that one writes in a style that is natural to them; whites writing in idioms that makes sense for Mance Liscomb is clearly insulting to black musicians and black culture in general. It is a not so subtle form of racism: it says "I think you're exotic, not quite human, something wholly "other" than normal. I will take your funny sounds and use them to decorate my cosmology." Absent the absolutist argument that only black musicians have the right to play blues and are the only ones who can have anything authentic expression (it's a powerful argument), the bottom line of the blues is the clear, simple, emotionally honest expression of one's experiences. That would mean that one find their own voice, something they can bring of themselves to the music they desire to perform and make it genuinely personal. There is a difference, a fine one, between having a personal style greatly influenced by black music and singers and one that slavishly tries to impersonate the sound, causing all sorts of suspicious Rich Little-isms. Those influenced by black artists but who have their own style, free of affectation: Butterfield, Mose Allison, Van Morrison, Tom Waits. Those who fail: Jagger, when he sings blues, Peter Wolfe, others galore. Wolf is listenable and usually effective as vocalist and frontman, but he never convinced me that his style was cleverly constructed, contrived. I won't go as far as to say he's guilty of minstrelsy, but his banter where spews hip argot, rope-a-dope rhymes and other offerings of hep-cat impersonation, comes off as cartoonish, stagy, really stereotypical of black performance; whether Cab Calloway or James Brown or an inspired preacher sermonizing from the pulpit of a black church, Wolf's machine gun is appropriation straight out. I had often wished he'd just keep his mouth shut and just sing.Yes, I realize the irony of the last sentence, but I think you see my point even if you might not agree with it. J.Geils is a band I've enjoyed a great deal over the last few decades, but there are times when Wolf's unreconstructed enthusiasm turns into caricature and stereotype. He reminds me of someone trying to beat his influences at their own game rather than forging something that is really his own.

As to the matter as to whether Bruno Mars , who is not black, is appropriating black music and an aesthetic born of African American experience, created by talented black artists, well…I don’t know the man’s music, let alone his version of Black Style. I will him be and not mention him again in this harangue. Appropriation has been with us forever, although I would suggest that the non-black musicians playing music that is African American in origin have, for the most part, a genuine love of the sounds they've been exposed to. Theft is theft and black creators must be located, credited and their families paid for the use of the bodies of work that formed the foundation for a huge amount of American culture and a character, but at the same time it seems reductive and ironically bigoted to suggest that only black musicians have the right, let alone the sole ability to make authentic jazz, blues, or rhythm and blues. Forcing matters of creativity into a any kind of requirements for acceptance is absurd and contrary to what art is supposed to do, the process through which an individual--an artist--experiences the world and , through the use of whatever medium moves him enough to create objects of beauty of contemplation that hadn't existed before. Pretty much going with Marcuse on this one, as in his bookd the Aesthetic Dimension, where he argues that Society, The Establishment, the Powers that Be, need to leave the artists and allow them to perform their task with their art making, to produce joy. Otherwise, if held to aesthetic principles that are contrary to inspiration, it ceases to be art. It is Propaganda. We do not need an American version of Soviet Realism, no matter where it comes from. It goes to authenticity that one writes in a style that is natural to them; whites writing in idioms that makes sense for Mance Liscomb is clearly insulting to black musicians and black culture in general. It is a not so subtle form of racism: it says "I think you're exotic, not quite human, something wholly "other" than normal. I will take your funny sounds and use them to decorate my cosmology." Absent the absolutist argument that only black musicians have the right to play blues and are the only ones who can have anything authentic expression (it's a powerful argument), the bottom line of the blues is the clear, simple, emotionally honest expression of one's experiences. That would mean that one find their own voice, something they can bring of themselves to the music they desire to perform and make it genuinely personal. There is a difference, a fine one, between having a personal style greatly influenced by black music and singers and one that slavishly tries to impersonate the sound, causing all sorts of suspicious Rich Little-isms. Those influenced by black artists but who have their own style, free of affectation: Butterfield, Mose Allison, Van Morrison, Tom Waits. Those who fail: Jagger, when he sings blues, Peter Wolfe, others galore. Wolf is listenable and usually effective as vocalist and frontman, but he never convinced me that his style was cleverly constructed, contrived. I won't go as far as to say he's guilty of minstrelsy, but his banter where spews hip argot, rope-a-dope rhymes and other offerings of hep-cat impersonation, comes off as cartoonish, stagy, really stereotypical of black performance; whether Cab Calloway or James Brown or an inspired preacher sermonizing from the pulpit of a black church, Wolf's machine gun is appropriation straight out. I had often wished he'd just keep his mouth shut and just sing.Yes, I realize the irony of the last sentence, but I think you see my point even if you might not agree with it. J.Geils is a band I've enjoyed a great deal over the last few decades, but there are times when Wolf's unreconstructed enthusiasm turns into caricature and stereotype. He reminds me of someone trying to beat his influences at their own game rather than forging something that is really his own.Saturday, February 2, 2019

THE MESSAGE AND THE MESS IT MADE

Debating what constitutes authenticity is a nice way to chase your tail, but is a fun way to pass the time when there's nothing else making demands on your time. It's not a waste of time since it is a way for us to define and articulate What Matters in life beyond our bond with the Banks and the Legal System. It is what makes life a pleasure, and a large part of that pleasure is maintaining the capacity to be pleasantly surprised.I've preferred to remain agnostic in matters of musical taste; pragmatic might be a better word. Or perhaps my tastes merely change with time. In any event, I tend to think that anyone committed to trying to make living playing music and performing, activities from which there are no guarantees of financial security (or even an audience) can't help but be sincere. One might dislike the motive or the personality, but the emotion is authentic enough. Better to consider whether the music is at least honest, or better yet, if it's done well: whether music, lyrics, voice, style work on their own terms, makes for a more interesting set of topics, and a more compelling record collection. What those terms turn out to be might be, at first, seemingly unacceptable or contrary to everything you held as essential to quality. But to paraphrase a famous line contextualizing Modern Art, most original art forms seem at first ugly and horrible; they emerge ahead of the curve and the rest of the culture has to catch up. Not everything gets past the finish line, though, as a review of your record collection reveals. I'd wager we all have many albums from bands and artists we thought were heavy and groovy back in the day that now makes us scratch what's left of our hairline, wondering what we were thinking.

It was after I slid into my forties where the other songs and albums by Zeppelin reemerged on my radar and revealed a band that was more diverse, musically, than the popular invective allows. Where I lived at the time, Zeppelin fans were just as likely to be listening to the Band, Van Morrison and CS&N, along with other folks "sissy" artists as they were the macho sounds of hard rock. Like the Beatles or Steely Dan, Led Zeppelin were studio artists, where the studio was the proverbial third instrument. Live, they were one of the worst bands I've ever seen--though they sounded pretty damned good when I saw them in '67 (?) on their first US tour with Jethro Tull--but in the studio, their music was finessed and honed, typical in those days. For all his faults as a faulty technician in live circumstances, he is a producer who brought a fresh ear to the recording process and came up with ideas that circumvented the routine dullness and rigor that's become the bane of less able hard rock and metal bands after his Zeppelin's break up.

The only real bad aftershock of " Sgt Pepper's" and other "concept albums" from the period was the mistaken notion by other artists that there had to be one grandiose and grandiloquent theme running throughout both sides of their albums in order for their work to be current with the mood of the art rock of the period. The Beatles succeeded with "Sgt. Pepper", "Magical Mystery Tour", and, and "Abbey Road" ( easily their most consistent set of material, I think) because they never abandoned the idea that the album needs to be a collection of good songs that sound good in a set: overlapping themes, lyrically, are absent in the Beatles work, unless you consider the reprise of the Pepper theme song on a leitmotif of any real significance (its use was cosmetic), although musical ideas did give the feel of conceptual unity track to track, album to album. Lennon and McCartney and Harrison's greatest contribution to rock music was their dedication to having each one of their songs be the best they could do before slating it for the album release. For other bands, the stabs at concept albums were routinely disastrous, witnessed by the Stones attempt to best their competitors with the regrettable 'Satanic Majesties Requests". The Who with "Tommy" and "Who's Next" and the Kinks, best of all, with "Lola", "Muswell Hillbillies" and "Village Green", both were rare, if visible exceptions to the rule. "Revolver" and "Yesterday and Today" are amazing song collections, united by grand ideas or not. I buy albums, finally, on the hope that the music is good, the songs are good, not the ideas confirm or critique the Western Tradition.

The conventional wisdom is often wrong, but not always, and I think the popular opinion that Sgt. Pepper is a better disc, song by song, than Satanic Majesties is on the mark. Majesties had The Stones basically playing catch up with the Beatles with their emergent eclecticism and failing, for the most part. That they didn't have George Martin producing and finessing the rough spots of unfinished songs marks the difference. Majesties, though does have at least one great song, "2000 Man", and a brilliant one, "She's A Rainbow" For the rest, it sounds like a noisy party in the apartment next door. The album sounds like a collection of affectations instead of a cohesive set of songs. Cohere is exactly what the tunes on Pepper did, good, great, brilliant, and mediocre. The sounded like they belonged together.

POWER TRIOS, POWER TRIPS, POWER ENNUI

I like loud and distorted guitar, old school, in the form of jamming power trios, those guitar-bass-drums shootouts where the downbeats started at debated counts and the length of improvised middle section was undetermined and unpredictable. Improvisation, riffing, vamping, monochromatic chord mongering, the center portions of this species of spontaneous noise took it's stylistic cue from several generations of black American blues geniuses and took their clear, elegantly expressed formulations of anger, pain , dread and joy and tweaked the pentatonic elements to a narrowed strain of white male rage, performed at volume levels beyond endurance levels , with the nimble, simple, eloquent rhythms and solo configurations of guitar , harmonica, banjo being replaced with a waves of distorted notes bent to their furthermost pitch of emotional credibility.

It was perfect for the smoky ballrooms I went to in the late '60s, where the likes of Cream, Blue Cheer, Sir Lord Baltimore and Mountain belched, groaned and assaulted a beleaguered audience of addled brains with their instrumental abuse; on some nights the commotion and clamor reminded you more of a demolition derby instead of a unique engagement with a fleeting muse. The impact was more important than configuration. There was joy when, in Detroit where I lived, I came upon the MC5 and the Stooges. The 5 were every car Detroit had manufactured being tossed off the top of the Penobscot, the tallest building in town; they had a speed and power only the fury of an accumulating gravity could provide, and half the fun of watching these guys batter, abuse and flail their instruments while the wiggled and wrenched themselves in hip-thrusting deliriums was the expectation of their metaphorical car crashing, smashing into the hard, metal strewn concrete below. The Stooges were, on the other hand, the guitar that was tossed off with a violent fling at a bad rehearsal and left on, still plugged into the amp, humming and crackling the whole night; Ron Ashton's guitar work was perfect, imperfect, with a wood-chipper rhythm, a perfect three and two-chord background for Iggy Pop, who's psycho-sexual explorations into the outer areas of teenage impatience would make you think of a zombies severed arm. It still twitches across the blood, the hand is still making grasping motions for your neck, you realize that even death cannot stop this force that requires your attention.

ROCK AND ROLL IS NOW AN OLD MAN'S GAME

People who are cool are those who don't professionalize their names and become the odious species called "professional celebrity". Johnny Lyndon became a celebrity, famous for being the former Johnny Rotten. Grace Slick is cool because she retired from being a rock star when she realized she was too old too silly singing those old songs about the problems of youth. It seemed to her, shall we say, inauthentic. People who are cool are not, by default, nonconformist or anti-social or any of the other rebellious bullshit that is actually an identity we buy into by corporate marketing departments. Being cool is doing what you want to do, liking what you like, listening and reading and seeing what you want because they truly mean something to you; cool people really have no interest in trying to appear cool.

I would ask why are writers for online magazines and pop culture sites so eager to condemn their fellow citizens for not being just like them. The Sex Pistols were the result of clever marketing no less than the Monkees were back in the day. There was an unrepresented generation in the music marketplace and Malcolm Mc Laren, in his fashion, created a product, of which Lyndon was part of, to fulfill a need. Or at least create a "want", as Chomsky would argue. Lyndon bright enough to be aware of the contrived nature of the Pistols, a band that wanted to destroy the machinery that produced manufactured entertainment that was no less manufactured by the same methods and reasoning, but on the cheap. Being a real punk, ie, a habitual jerk, he set out to destroy his meal ticket. He asked if the audience felt cheated, a manner of pulling back the curtain on a variation of the star-maker machinery, but his willingness to expose the hype became an essential part of what became his act (or shtick). He made a living a being the former Johnny Rotten, a low-rent Oscar Wilde. He may have been speaking his truth, and bully, but he wasn’t wit and he wasn’t especially enlightening.

I would ask why are writers for online magazines and pop culture sites so eager to condemn their fellow citizens for not being just like them. The Sex Pistols were the result of clever marketing no less than the Monkees were back in the day. There was an unrepresented generation in the music marketplace and Malcolm Mc Laren, in his fashion, created a product, of which Lyndon was part of, to fulfill a need. Or at least create a "want", as Chomsky would argue. Lyndon bright enough to be aware of the contrived nature of the Pistols, a band that wanted to destroy the machinery that produced manufactured entertainment that was no less manufactured by the same methods and reasoning, but on the cheap. Being a real punk, ie, a habitual jerk, he set out to destroy his meal ticket. He asked if the audience felt cheated, a manner of pulling back the curtain on a variation of the star-maker machinery, but his willingness to expose the hype became an essential part of what became his act (or shtick). He made a living a being the former Johnny Rotten, a low-rent Oscar Wilde. He may have been speaking his truth, and bully, but he wasn’t wit and he wasn’t especially enlightening.

He was guest VJ on MTV decades ago, post –Rotten and Pill and here he was easing into the one marketable guise he had remaining, the go-to “survivor” of a heady period at the popular culture margins. He was to introduce clips from newer bands and comment briefly when they were done, a negative bon mot before the station cut to one of their endless streams of commercials.

He was guest VJ on MTV decades ago, post –Rotten and Pill and here he was easing into the one marketable guise he had remaining, the go-to “survivor” of a heady period at the popular culture margins. He was to introduce clips from newer bands and comment briefly when they were done, a negative bon mot before the station cut to one of their endless streams of commercials. After a Jesus and Mary Chain video had played, the image faded and the camera opened up on Lyndon’s constipated visage. “Oh, that was awful. They are so derivative of the Velvet Underground…” I might agree with Lydon if I knew more about the JAMC songbook, but the remark had no impact, no sting, it cut to nothing at all; he seemed bored with his whole act of being the cynical, seen-it-all rock and roll revolutionary who must manage simulacra of disgust to sustain a paycheck. Not hip, not cool. Capitalism wastes nothing, even the shards of the artifice someone has blown up with some subdued version of the truth. Remember Marcuse's idea of "repressive tolerance"? That was the idea that democratic capitalism is so insidious that it has an organic function to nullify the revolutionary potential of various cultural and social upheavals by permitting those ostensible enemies of order full legal expression of their style, their manner, their ideology. The goal is fairly obvious, you negate revolutionary change by allowing those who expose and espouse radical transformation to vent and argue their position and allow the creative expressions they generate to emerge more or less unmolested.

Everything we create is transformed into product or material that can be used to manufacture variations of the false utopia we bought into in the first place. Nothing is wasted. The smashed idealism we tossed out is reassembled and given a new coat of paint and then sold to someone else who is trying to trust the authority of their senses. Che, Lenin, Mao, Trotsky and Karl Marx himself adorn t-shirts, mugs, and keychains manufactured in Free Trade countries at what amounts to slave wages, the rebel-yell tradition of rock and roll is codified and neutered with a Hall of Fame, and what could be instructive criticism for those of us to change our behavior and get involved in the politics of their lives is made irrelevant by being turned into feel-good cynicism suitable for coffee mugs, shirts, greeting cards and witless situation comedies. Johnny Lyndon is a tool, a professional celebrity, and his greatest accomplishment was in creating a generation that had no greater desire than to be professional celebrities as well. Warhol's over-repeated remark about everyone in the future being famous for fifteen minutes not only came to fruition but had become something of a religion, sphere of thinking wherein the hapless and the moronic considered their ordained destiny to be famous, rich, above accountability. The whole withering -away- of- the -state endgame in Marxist theory was a pie in the sky, I think, a trope that replaces Christianity's doctrine of Eternal Life in Heaven with a promise that amounts to the same thing.

Happiness and fulfillment are forestalled until certain unattainable and unverifiable conditions are met. The transformation is never witnessed as advertised. This seems to be same with how things are sold to customers--you are not perfect or really at ease until you own this. Again, we never really see the transformation of ordinary people into extraordinary ones, but we can witness the accumulation of useless things, received wisdom, dime store attitudes displayed as philosophical distinctions. Being hip or cool, it seems, seems to part of this whole mentality that there is an exclusive club one must pay to join in order to get a glimpse of the heaven they’ve taken out a prescription to. This is the reverse of what being cool was all about, which was living a life that was modulated to not absorb the static, babble and decaying artifices society put upon you, to conduct oneself with a knowledge that horrible violence and obliteration can be visited on you any second and, with knowledge of that, make life meaningful by making authentic choices as to what you want to do and to take responsibility, full claim, to the results (and consequences) of those actions. Creative commitment is what that is called, an element in the overly abstruse doctrines of existentialist thought.

A RETICENT RECOLLECTION

| BEEN SO LONG: My Life and Music By Jorma Kaukonen |

However reticent Kaukonen was to speak with the press at the peak of his fame with the Airplane (and later with Hot Tuna, his long-term folk and electric blues project with JA bassist Jack Casady), the author’s memory seems to serve him well in these pages. A second generation American of Finnish descent born in Washington DC in 1940, young Kaukonen had already seen much of the world, particularly Philippines and Pakistan courtesy of his father’s diplomatic corps assignments. His early years seemed a case of accidental wanderlust, his family from moving city to city, country to country, with Kaukonen, easily making friends in each new home though, it seems, shared interests in music, cars (“gearheads” as they called themselves) and, to be sure, girls. While in Washington he acquired a guitar and began learning traditional folk songs, learned the advantages of keeping his guitar tuned, and made a lifelong friendship with future JA bassist Jack Casady. What Kaukonen realized was that playing music was pretty much what he wanted to do, and muses that music seemed the elixir that made brought a dimension to his life than just merely existing and putting with boring jobs and mean people. Laconically and tersely, he concludes “Music seemed to me to be the reward for being alive.”

The first half of the book is full of reminisces about his family, his two sets of grandparents from Europe in the quest for the opportunities migrations to America promised, and he speaks fondly, lovingly of his parents, aunts and uncles and shares what he recalls of their expectations of a new life in the promised land. Most tellingly, though, was Kaukonen’s seemingly slow but eventual emersion into music. We see in negotiation with his father for a guitar, his playing DC clubs with Casady, with fake IDs, when Casady was playing lead guitar and Kaukonen played rhythm. And we see his growing interest in folk music styles that would become the defining essence of what would become his electric guitar style with Jefferson Airplane. Developing into a fine finger picker and with an affinity for the simple and elegantly articulated patterns of folk-blues, Kaukonen incorporated these techniques into his eventual electric work for the Airplane, giving them a rattling guitar sound unique in an era where every other guitarist fashioned Clapton impersonations. Kaukonen’s style slid and slithered, his leads full of peculiar tunings, odd emphasis on blues bends, and a jarring vibrato that made teeth chatter and nerve endings fire up. It was a style that informed the Airplane’s best songs— “Lather”, “White Rabbit”, “Greasy Heart”—and which was a sound that was an essential part of the complex and wonderful weave that characterized this band’s best albums, from Jefferson Airplane Takes Off through Volunteers.

At a point, Jefferson Airplane was among the top bands of the era, one of the top bands in the world, originating in the countercultural environs of San Francisco and adventuring beyond those city blocks to perform historical rock gigs such as the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. It was something of a charmed life, Kaukonen was earning a good amount of money. He was, he admits, willing to start spending it, buying homes, new cars, new equipment. The band was at the top of their game, and on a Dick Cavett, Show following the last night of the Woodstock Art and Music Festival, a myriad of performers—David Crosby, Joni Mitchell, the Airplane, Steve Stills among them—sat around a rather casual set for the program and bantered breathlessly about the monumental experience they’d all just been through. In the afterglow, at that moment, it seemed as though Ralph Gleason’s mid-Sixties prediction in Rolling Stone that the Sixties Youth, spearheaded by the music, musicians, troubadours, and poets of the time, would change America profoundly, enact a revolution without bloodshed or bombs. The music would set you free. Believe me, I was there, watching the Cavett show at least in my parent’s basement TV, as well as reading the newspaper and 6pm news reports on the massive concert. For a few minutes, just a few, it all seemed possible, especially when watching the beautiful and brilliant Grace Slick and the Teutonically authoritative Paul Kanter lay it out what many took to be a forecast of the American future. Kaukonen was on the set as well, in the background, sitting with his guitar. He was happy to let Slick and Kanter do the talking; as reiterates through the narrative that he was happy to play his guitar and let others be the prophets.

There is much ground Kaukonen tries to cover in Been So Long, but there is a lack of urgency on the author’s part to offer detail, specifics, characteristics or insights connected to the material progression of his story. He is an able writer that conveys a personality that’s sufficiently humble after the long, strange trip he’s been on. He has gratitude for the gift that has been bestowed upon him and humble in the face of the hard times and deviltries he’s survived. But there is a kind of cracker-barrel philosophy in tone, a succession of incidents, occasions, fetes, celebrations and disappointments in his life, told in sketchy detail summarized with a cornball summation, a reworked cliché, a platitude passing as hindsight. He mentions family, wives, children, famous musicians in a continual flow of circumstances, but does not actually say much beyond the convenient sentiment when you expect him to give a hard-won perspective of his adventures before and after the Rock and Roll Life. Despite having a life’s story that might otherwise seem impossible to tell in a dull manner, Kaukonen is intent on doing just that.

He does not tell tales out of school, he doesn’t reveal the quirks of his friends. what he might consider the essence of their genius; structurally the book reads as if it were compiled from notecards and handwritten journals, arranged in order (more or less), assembled for a rapid walk- through rather a revelation of what drew an artistic temperament to this kind of life at all. Kaukonen’s reticence to write more deeply prevents a fascinating and unique tale on the face of it from being more compelling. It’s as if he’s talking about things he would rather not disclose; the half-measured commitment shows up when he mentions his increasing reliance upon an addiction to alcohol through the book’s chapters. Using phrases from the principal writings of Alcoholics Anonymous as well and peppering his text with 12 step mottos, it’s apparent from those in recovery where the musician got help for this alcoholism. A large part of the A.A. program is for members to find a God of their understanding, a power greater than oneself which can help them with their problem. For those who have a “God Problem”, the fellowship also refers generically to “a power greater than oneself”. A god of one’s own understanding? Fair enough, but Kaukonen here takes to writing God as “G-d” for reasons that remain explained. It’s one thing to not demand that others have the have the same theology as yourself, but it’s another to routinely omit an offending “O” when the world God comes into expressive play. Being more forthcoming on this quirk, offering a reason for the eccentric use, would have offered more light on the outline Kaukonen offers. It is a small mystery, an annoying one, a recurring bump in the road that stops the reader; what is Kaukonen not telling us?

Perhaps an as-told-to memoir like Keith Richard’s memoir Life would have eased more nuance and insight and crucial detail from the hesitant Kaukonen. Richards, speaking at length and on-the-record with collaborator James Fox, the Rolling Stones guitarist speaks frankly and at length about the highlights and low spots of his life in music; free to speak as he pleased to Fox’s probing questions and not having to worry about censoring himself while at the typewriter or with pen-in-hand, Life is a witty, harrowing, bristling account of one remarkable musician’s life. On the surface, Kaukonen’s tale is as full and intriguing as a rock and roll biography requires— worldly as a young man, ROTC, a lover of music and cars, a founding member of one of the most significant bands of the Sixties in the midst of a major cultural revolution, drugs, money, fame, glory, flaming out, regrouping—the outline is here, yet Kaukonen does little to flesh it out or reveal the sex, sizzle, and drama under the facts and their note-card descriptions. Richard’s work with a collaborator allowed his mouth to run as long as it needed to tell the best story he had, his own, the final payoff is an engrossing read blessed with Richard’s hard-won and refreshingly offhand wisdom. The Jefferson Airplane guitarist is not so garrulous, is reflectively taciturn and terse, in fact. One needs to respect his right to tell his story as he sees appropriate; the shame is that what is likely a great story doesn’t so much get told as mentioned in passing.

Been So Long remains a fascinating read and is an interesting addition of first-hand accounts of the psychedelic revolution in the 60s from a key player. The irony here is that Kaukonen does indeed remember the decade—he just doesn’t see the need to get into the weeds, dig in the dirt and relate something fuller, an account of a life fully lived.

(This first appeared in the San Diego Troubadour. Used with kind permission)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)