(This originally appeared in a another version in the San Diego Reader, 1975).

In the waning days of 1974, as the hoi polloi queued for Led Zeppelin’s latest eruption of amplified bravado, the rock critics, their brows knitted in a familiar fret, awaited Bob Dylan’s *Blood on the Tracks* with the hushed anticipation of cloistered scholars. The masses could revel in their sonic bacchanals, all sweat and decibels; the critics, those fastidious sentinels of taste, craved something weightier, a voice to parse the nation’s disquiet. Dylan was no mere troubadour—he was a chameleon, a poet of the asphalt and the soul, whose nasal hymns had once seemed to reorder the stars. His pronouncements demanded attention; symposia were convened, pens poised for annotation. Perhaps this exaggerates the fervor, but for years, the press had swaddled him in a cocoon of expectation, their adulation both tribute and burden. Now, rumor held that *Blood* was his homecoming, a retreat from the facile mysticism and barroom bonhomie of recent years. I settled into my chair, skeptical, curious for the inevitable sleight of hand. The critics, it appeared, had already uncorked their champagne.

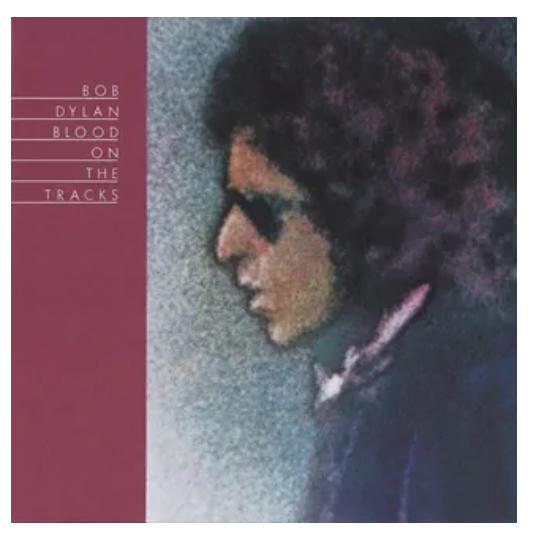

*Blood on the Tracks* is Dylan as his acolytes remember him: the harmonica’s thin, asthmatic wail, like a wind skittering through a deserted alley; a voice that stumbles and gasps, tethered to no rhythm save its own caprice; lyrics that cascade in a torrent of images, defying meter yet thick with private meaning. It is the Dylan of yore, the Greenwich Village bard reborn, and the critics greeted him with open arms. The counter culture's tip sheet *Rolling Stone*, in high ceremony, banished its usual reviews to make room for a pair of ponderous essays—Jonathan Cott and Jon Landau, high priests of the moment, flanked by a chorus of eminent voices, with only Dave Marsh’s dissent piercing the hosannas. The verdict was near-unanimous: a triumph, a poet’s return, a tapestry of genius. Familiar praises, repolished to a gleam. Yet what unsettles is the ardor itself, a kind of collective yearning. From my modest perch in Clairemont, far from San Francisco’s bohemian haze—where rock stars seem to embody the fan’s unspoken longings—*Blood* feels less like a revelation than a simulacrum, a deftly crafted echo of a voice grown faint. Dylan sounds detached, a performer playing himself for an audience he no longer trusts. It is as if, wearied by the chase, he has lain down in the snow, offering his bones to the circling pack. The image is not a kind one.

Once, I too fell under Dylan’s spell. In the acne-scarred fervor of junior high, his sneer was a talisman, his mystique a lantern in the suburban dusk. He was untouchable—defiant, electric, a man who spurned the world’s judgment with a curl of his lip. His life was a mosaic of excess: the endless road, glimpsed in the flickering frames of D.A. Pennebaker’s grainy verite *Don’t Look Back*; the rumored pharmacopoeia—amphetamines, perhaps heroin, a brush with acid; whispers of liaisons with Allen Ginsberg, apocryphal or not, that lent him the sheen of a Byronic rogue. He was a poet of America’s underbelly, his songs spilling forth like dispatches from a frontier aflame. *Highway 61 Revisited*, *Bringing It All Back Home*, *Blonde on Blonde*—these were his gospel, a sound sui generis, jagged and alive. His early folk forays were a young man’s masquerade, aping the ghosts of blues and hillbilly bards; what followed *Blonde* was a retreat into domesticity, a softening that drained his fire. *John Wesley Harding* offered glimmers—parables refracted through a biblical lens—but it lacked urgency. *Nashville Skyline*? A friend, now estranged, once claimed it taught him “rednecks are human too.” I swallowed a grimace.

To hear *Blood on the Tracks* is to confront the ghost of the Dylan devotee. In 1966-67, he was our mirror, our savior, singing for the awkward, the inward, the boys scribbling verse in lamplit bedrooms, haunted by the draft and the weight of their own inertia. Life was a cocktail of dread and ennui, the suburbs a velvet cage. Dylan’s tangled curls, his reedy defiance, his “go to hell” lyrics—they were a dream of escape, a way to defy the cul-de-sacs without stepping beyond the lawn. He carried our burdens, a scapegoat for a generation too cosseted to follow Kerouac’s dusty road. Time dulled that enchantment. I turned to rawer sounds—Grand Funk’s blunt force over the Moody Blues’ ethereal drift—seeking not insight but obliteration. Dylan, stung by the tepid sales of *Planet Waves* and *Before the Flood*, chose to appease his flock. *Blood* is the result, but it is a warped mirror, reflecting a past that no longer breathes.

If *Blood* is a feint, it is also a confession. Dylan abandoned his speed-freak persona for survival’s sake—such fires consume their keepers. To demand that old ferocity is to court a corpse. Recapturing *Highway 61* is like bottling a storm. So, with coffee cooling and cigarette ash lengthening, I watch the record turn. “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome” begins—Dylan’s voice nasal, laced with a theatrical sincerity, as if Elvis were crooning for a supper club. The guitars plod, the harmonica sputters like a failing engine, a nod to Gerdes Folk City for those who missed the myth’s first act. He veers off-pitch, scatters references to Rimbaud and Delacroix, teasing the annotators. Who is this for? “Tangled Up in Blue” fares better, its voice truer, but it lacks revelation. “Simple Twist of Fate” stumbles. “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” reaches for *Highway 61*’s surreal shimmer but collapses into cliché, a tale told too often. The platitudes gather like dust, stifling the air. My cigarette burns to its nub; I resist the urge to halt the needle. This is a bitter pill from a man who once seemed to hold the cosmos in his throat. Yet I gleaned my Dylan truths long ago—I should not mourn. New voices beckon: Little Feat’s earthy pulse, Roxy Music’s urbane glitter, Harvey Mandel’s sinuous lines, perhaps Queen’s baroque audacity. The band lumbers on, Dylan mimicking himself with a faint, knowing smile, as if he sees through his own charade. The parade has passed, its banners faded. The record ends, the arm lifts. I turn on the radio, and Led Zeppelin’s primal wail floods the room—a coarser, truer song.