|

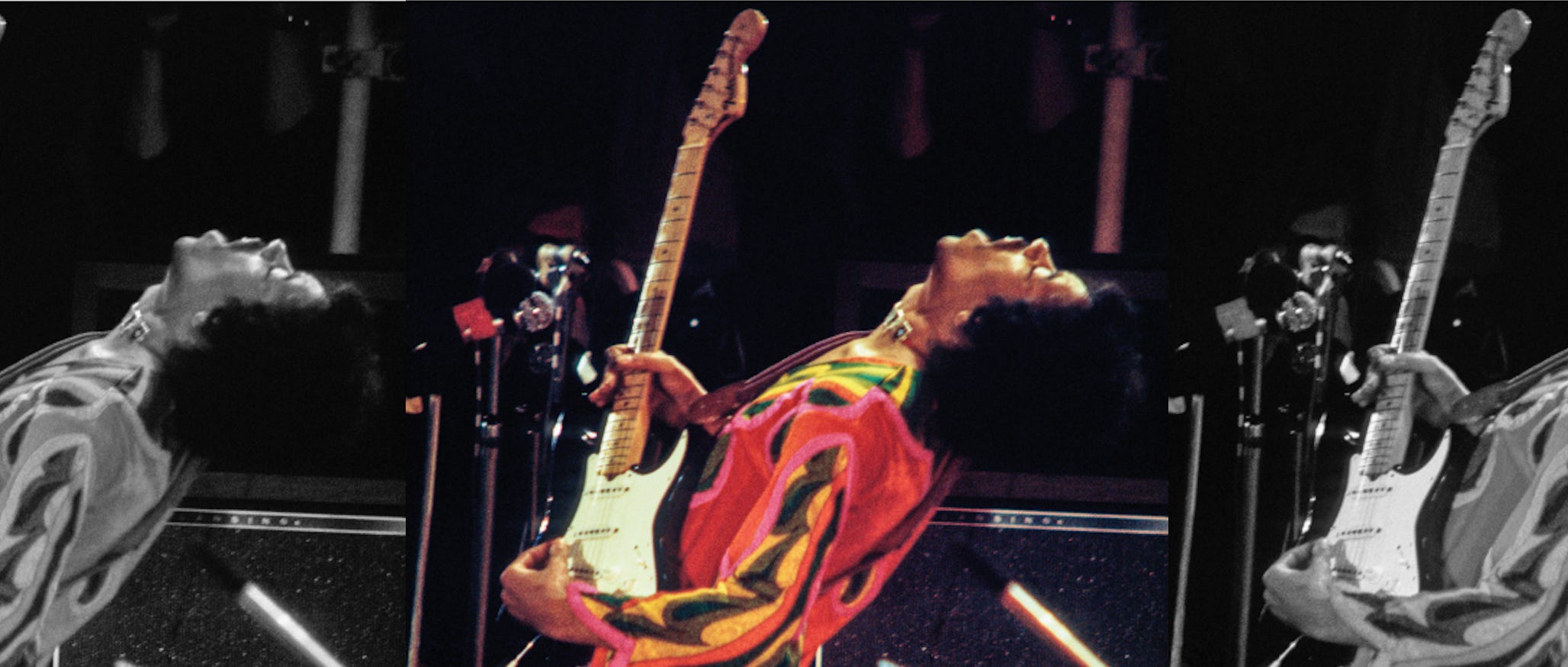

| photograph by Jim Marshall |

An old peeve, this: Bob Dylan is not a poet. He is a songwriter. What he does is significantly different than what a poet does. In any relevant sense, the best of what poetry offers is read off the page, sans melody from accompanying guitar or piano and a convincingly evocative voice. The poet's musical sense, rhythmic properties, and other euphonious qualities are derived from the words and their clever, ingenious combinations alone. A reader may appreciate the words, the rhymes, the cadences, the melodious resonance, and dissonance, as the case may be, but all this comes from the poem's language alone, on the page, without music. The musicality we speak of when addressing such rich and soul-stirring sounds of nouns and adjectives conjoined has everything to with the poet extending the limits of everyday speech. You can read Shakespeare to full literary potential, I think, because his verse, in the guise of dialogue, still satisfies as writing, with metaphors, rhythms, cadences swirling and ringing to a heightened sense of what the complexity of human emotion can sound like if there were words, allusions, similes, and metaphors that could give life and texture for what are, in his plays, inchoate feelings brewing at some base level of the personality before the mind can give them an articulate if flawed rationale.

It was the task of Shakespeare, the poet, and the playwright combined to give verbal music to what were speeches that made private thoughts, half-plotted schemes, inarticulate resentments, paranoia, the whole conflicting brew of insecurity, self-doubt, and malevolence into something that was the equivalent of music, a sweet and stirring sound that bypasses the censoring and sense-making intellect and which makes even the foulest of schemes seem just and only natural. The writing approximates music from the page and provides for a more complicated task when considering our responses to a provocative set of stanzas. Dylan is a songwriter, a distinct art form, and his words are lyrics, which cannot be experienced to their fullest without the music that goes along with them. One may, of course, hum the melodies while pouring over the lyrics and mentally reconstruct of listening to songs of an album, but this proves the point. Of themselves, Dylan's lyrics pale badly compared to page poets. With his music, the lyrics come alive and artful, at their best. They are lyrics, inseparable from their melodies, and not poems, which have another kind of life altogether.

The lyrics are flat and unremarkable save for their strangeness, which is not especially interesting in verbal terms. With music, voila! Transformation. This is a condition that makes what Dylan does songwriting, not the writing of poetry. These are distinct art forms with features and rules of composition that are crucial and non-negotiable. Cohen is an interesting case since he inhabits several writing mediums, IE, novels, poetry, plays music. He's not especially prolific in any of these areas--over the forty-plus years that he's been on my radar, his output has been meager, albeit high quality--but it occurs to me that he's more of an actual writer than Dylan is. They are different sorts of geniuses. Cohen, of course, is a novelist overall—“Beautiful Losers,” “The Favorite Game”--and a poet, someone wholly committed to making the words from their own music, rhythm and power so that the sort of splendid, soul-racked suffering he specializes in, that deliciously wrought agony that's midway between spiritual experience and sexual release, is fully conveyed to the reader and made as felt as possible.

Cohen tends the words he uses more than Dylan does; his language is strange and abstruse at times, but beyond the oddity of the existences he sets upon his canvas, there exist an element that is persuasive, alluring, masterfully wrought with writing, from the page alone, that blends all the attendant aspects of Cohen's stressed worldliness-- sexuality, religious ecstasy, the burden of his whiteness-- into a whole, subtly argued, minutely detailed, expertly layered with just so many fine, exacting touches of language. His songs, which I find the finest of the late 20th century in English--only Dylan, Costello, Mitchell, and Paul Simon have comparable bodies of work--we find more attention given to the effect of every word and phrase that's applied to his themes, his storylines. In many ways, I would say Cohen is a better lyricist than Dylan because he's a better writer overall. Unlike Dylan, who has been indiscriminate for the last thirty years about the quality of work he's released, there is scarcely anything in Cohen's songbook you would characterize as a cast-off.

Cohen takes more care in words he selects to tell his tales. He creates his moods, as he provides a sense of location, tone, and philosophical underpinning while also working subtly working to suggest the opposite of whatever mood he might be getting at. Cohen is simply more careful than Dylan.

In word selection, more discriminating; the architecture of literary influence is displayed in the disciplined rhymes of Cohen's parable-themed lyrics, elegantly so. It is, to be sure, a matter of choice how a writer manages their word flow. Cohen's writing has a sense of someone who labors hard to make the image work, to have that image compliment and make enticingly evocative a scenario that starts off simple and then arrives at a moment of fatalistic surrender to powers greater than oneself, both sensual and spiritual. My feeling for Dylan's method is that he is an admirer of what Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac regarded as Spontaneous Bop Prosody, a zen-like approach to an expression where it was regarded that the first thought was the best thought one could have on a subject.

Good poets, great poets, are writers when it gets down to what they do, and it’s my feeling that Cohen’s experience as a novelist, short story writer, and playwright has given him a well-honed instinct for keeping the verbiage to a minimum. This is not to say Cohen is a chintzy minimalist, such as Raymond Carver, or that fewer words in a piece are, by default, superior to longer word counts; rather, Cohen just has a better sense of when it’s time to stop and develop a lyric further.

Dylan's genius is closer to the kind of brilliance we see in Miles Davis, where the influences of unlike styles of music and other elements-- traditional folk, rock, and roll, protest songs, blues, country, French symbolism, Beat poets--were mixed in ways that created a new kind of music, and required a new critical language to discuss what it was he had done with the influences he'd assimilated, and the range of his influence. It is possible to look at aspects of Dylan's art. Fine individual strands wanting--his lyrics may be unfocused or strange for their own sake, his melodies are either borrowed or lack sophistication, his singing is nasal and grating--but taken together, music, words, voice, instrumentation fused, one experiences catharsis, power and galvanizing mysticism in the best recorded moments. "Ballad of a Thin Man" is a flat, curious scribble of a lyric read by itself. Still, with the minor key intonations of Al Kooper's keyboard and Mike Bloomfield's interned guitar, coupled with Dylan's leering, a snarling dramatization of the lyric, we have an art that is riveting n terms that are purely musical; yes, one might go on at length and create a cosmology of what Dylan's lyrical creations make of the experience, but the emphasis needs to remain on the whole.

" It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)"is a terrific, innovative song lyric, and as a lyric does not have the same power as a well-written poem has on the page when that lyric hasn't the music to give it momentum. The power of the lyric has a sustained "oh wow" element, one line after another summarizing the sad state of the Perfect Union, the Idealized world in harsh, ironic terms, each image and beat of the intoned images, critical, lively, surreal in a seamless mash-up of dissimilar concepts, are lifted, foisted, tossed to the listener by the steady and firm strums of the simple guitar Dylan maintains. Lyrics have their advantages and can be quite artful and subtle, but I maintain that they're a different art form; the words are subservient to the song form, where poems of every sort are autonomous, structures made entirely of language. (Unless, of course, you're a Dada poet who just arrived here with a time machine).

"Desolation Row" and "Visions of Johanna," two songs from what I think is the center of Dylan's greatest period as a song-poet, if you will, likewise are not to make their fantastic excursions through Daliesque landscapes alone on the page, as flat print. Dylan's chords, his voice, and his forward-march rhythms are what make these extended lyrics crisp and suggestive of metaphysical chaos under a thin the thin guise of civility and reason. Drums, organs, twangy and tuneless guitars, police sirens, his braying voice bring a dimension to the lyrics that aren't there without it. Dylan's lyrics especially--more so than Cole Porter, more so than Chuck Berry, more so than a host of his contemporaries--are not self-sufficient as page-poets are with their work. It can be argued that what Dylan has done is more complex, subtler, and requiring a new vocabulary to discuss than what poets have done, and something I would subscribe to on principle. Dylan remains a songwriter first and foremost and a poet only through loose analogy. In all, Dylan's lyrics serve the musical experience, the concept of a song, which makes Dylan a songwriter of genius, but not a poet. When they are writing poetry and not novels or songs of their own, poets are committed to making language and language alone, the means through which their ethereal notions will be preserved. Successor failure on their part depends solely on how well they can write, not strum a guitar or croon a tune.

____________________________________________________________

2.

I do admire the work of artists who remain interesting as they get older, but it is a fact that many writers, poets, songwriters do their best, most compelling work in their early years. Dylan is one of these--the greatest songs, in my view, were those that combined equal elements of Surrealism, Burroughs-inspired language cut-ups, blues and rural south music vernaculars, and heavy doses of French Symbolism by way of Rimbaud and Mallarme. This gave his stanzas a heightened, alienated feeling of sensory overload, making him the principal Lyricist of the bare existential absurdity that life happens to be. No one got to the infuriating heart of the sensation that life had ceased to mean anything after those matters that "mean" the most to us--marriages, friendships, tastes, financial security, spiritual or religious certainty--were changed, destroyed, or simply vanished. Dylan's writing was of the individual suddenly in the choking throes of uncertainty, batting back encroaching gloom with the kind of swinging, poetic wit that reassembles existence. The stance, a state, an aesthetic state of being that made it possible for him to fire on all cylinders for a good run of time. Generally, Dylan's poetic quality and intensity in the longs on the list I made are a substantial body of work that lines up perfectly with and matches the strongest work by Eliot, Pound, WC Williams, Burroughs Ginsberg. It is also not the kind of work you can keep doing for a lifetime; like Miles Davis, he had to. His mature work has often hit the mark and offers a long view of experience, especially moving. Just as often, I think he misses the mark and overwrites or is prone to hackneyed phrasing.

There is much quality to the later songs, but they are not among Dylan's greatest as a body of lyrics. Dylan is called more often than not a poet because of the unique genius of his best lyrics; I don't think he's a poet, but a songwriter with an original talent strong enough to change that particular art forever. I do understand, though, why a host of critics through the decades would consider him a poet in the first place. My list is the songs I think that justify any sort of reputation Dylan has a poetic genius. I like most of the songs mentioned above for various reasons other than the ones on my initial 35 choices; the longs there manage an affinity for evoking the ambiguities and sharp perceptions of an acutely aware personality who is using poetic devices to achieve more abstract and suggestive effects and still manage to be wonderfully tuneful. No one else in rock and roll, really, was doing that before Dylan was. On those terms, nothing he's written is quite at the level of where he was with the songs on my list; this list consists of the body of work that substantiates Dylan's claim to genius." Just Like a Woman" is one of the finest character sketches I've ever heard in a song. What's remarkable is the brevity of the whole, how much history is suggested, inferred, insinuated in spare yet arresting imagery. I rather like that Dylan allows the mystery of this character to linger, to not let the fog settle. It is the ambiguity that gives its suggestive power, and there is the whole element of whether the person addressed is a woman at all, but rather a drag queen. It's an open question; it's a brilliant lyric.

"Drifter's Escape "was on twice and is now a single entry. There is a concentration of detail in the lyric, a compression of Biblical cadence and sequence that makes the song telling and vivid not in its piling on stanzas but in its brevity. He does the same for "All along the Watchtower," which I regard as a condensed "Desolation Row," a commentary, perhaps, from the tour bus just passing through; the tour guide finally tells the driver, "there must be some kinda way outta here." I regard the true "poetry" of Dylan's music in the earlier music, where he is spectacularly original in how he forced his influences to take new shapes and create new perspectives. Post JWH, I just find too much of his lyric writing prolix, and meandering, time-filling rather than revealing; the surreal, fresh, colloquial snap of his language has gone and is replaced with turns of phrase that are trite, hackneyed, ineffective;' they strike my ear as false. Even "Blind Willie McTell," a song that has been persuasively defended by intelligent fans of Dylan's later work, strikes too many false notes for my tastes. Musically, it drags and philosophically seems a victim of convenient thinking, a PC version of Song of the South; some of the imagery is simply cloying and seems more suitable more for Gone with the Wind than a poet of arguable worth.

...See them big plantations burning

Hear the cracking of the whips

Smell that sweet magnolia blooming

See the ghosts of slavery ships

I can hear them tribes a-moaning

Hear that undertaker’s bell...

Really, that is awful, a dreadful presentation of atmospheric detail meant to create historical context and mood, but it trades on so many received ideas of slavery, racism, the south, et al., that the intent no longer matters. It strikes as more minstrel show than tribute. Had anyone submitted this to serious poetry (or lyric) writing workshop, it would have been handed back to us for revision, with the advice that we rid the narrative of the creaky, questionable window dressing? "When I Paint My Masterpiece" works wonderfully because of its lack of any messages about social justice. It works because it is a sharp, terse, vivid travelogue, vague and evocative in equal measure. The ambiguity and absence of relevance to anything other than Dylan's need to speak offhandedly about an interesting time in a particular character's life is what makes this song memorable.

Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You can almost think that you’re seein’ double

On a cold, dark night on the Spanish Stairs

Got to hurry on back to my hotel room

Where I’ve got me a date with Botticelli’s niece

She promised that she’d be right there with me

When I paint my masterpiece

Well, I had a feeling that the general good feeling this album conveys is that Dylan wasn't trying too hard to prove he's a genius. The record is straightforward, and the language is remarkably free of affectation, a tendency that has plagued him post-JWH. I especially like "Sign in the Window"; it has the sincerity and actual and momentary acceptance of where one happens to be in a certain part of life and offers a new set of expectations. The perfectly natural language here, good and unexpected rhymes, telling use of local detail that give us color and history without sagging qualifiers to make it more "authentic," the lyrics are a recollection of a trip, of places visited, of perspectives changing, a nice string of incidents in a language that sounds like a real voice telling real things, with genuine bemusement.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-399579-1267600816.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3002743-1372682484-6170.jpeg.jpg)